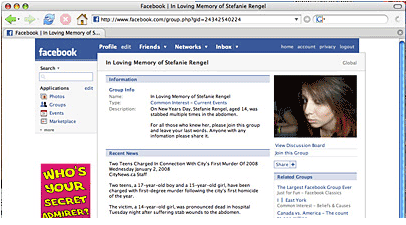

With the tremendous success and spread of social networking sites like Facebook and MySpace, along with home-broadcasting sites such as YouTube and Flickr, many people have become concerned about what effect they will have on our attitudes towards privacy. Now a new question has arisen: whether Facebook postings violate the Youth Criminal Justice Act if they identify suspects or victims covered under the act.

The first of two trials for the accused murderers of Stefanie Rengel, who was killed in January of 2008, is about to conclude. Unusually, although both she and those arrested for her murder were under eighteen, her identity has been released to the media. Normally, if a suspect is under eighteen the Youth Criminal Justice Act prohibits the publication of any information that might reveal their identity, including the identity of the victim:

110. (1) Subject to this section, no person shall publish the name of a young person, or any other information related to a young person, if it would identify the young person as a young person dealt with under this Act.

111. (1) Subject to this section, no person shall publish the name of a child or young person, or any other information related to a child or a young person, if it would identify the child or young person as having been a victim of, or as having appeared as a witness in connection with, an offence committed or alleged to have been committed by a young person.

Section 111 does allow the publication of the victim's name if his or her parents allow it, which Stefanie's have done. The two accused killers have been referred to in the press only by their initials, as is common practice if the accused is under eighteen. In this case it is little more than a formality, though, because both Stefanie's name and that of her suspected killers were published more than a year ago – on Facebook.

Against the law?

Opinions differ on whether postings to these Facebook groups – whose audience can vary based on the privacy settings chosen by the group's creator – would count as publication under the law. It's an issue nobody seems to be in a hurry to decide: Peel Constable Wayne Patterson, questioned by the Toronto Star, described it as “a good question,” adding “I guess it all boils down to whether Facebook is eventually determined by somebody that it is a publication.” Meanwhile Alain Charette, a spokesperson for the Department of Justice, told the same publication that the YCJA does apply to Facebook, and that “If it's about a violation, it's in police hands. If police get knowledge of that, it's for them to take it from there.”

In fact, this is not the first time the question has been raised of whether online postings count as publications: the Usenet group alt.fan.karla-homolka was blocked by numerous Canadian universities during the Paul Bernardo and Karla Homolka trials in 1993, due to fears that the universities might be violating a gag order against publication of the details of the crimes by allowing access to the group, which carried postings including just such details. No definitive ruling was ever made however, leaving it unclear whether the universities' fears were well-founded.

A growing problem

The Internet of 1993 reached few enough people that we could afford to leave the question for another day. With sites like Facebook growing at a rate of 250,000 new users a day, though, it has become clear that controlling information – even in cases like the YCJA, where it is done for arguably the best of intentions – has become much more difficult than it once was. The courts are still deciding just how much privacy can be expected on social networking sites; a Toronto judge recently ruled that even posts whose distribution is limited to Friends only must be disclosed if they are relevant to the case. (This ruling actually came from a civil trial, in which postings on the plaintiff's Facebook page were introduced to counter his claims of having been seriously injured in an accident, but the precedent would apply to criminal cases as well.)

Complicating matters still further is the fact that many of these sites' users are, themselves, young people: as Martha McKinnon, executive director of Justice for Children and Youth, told the CBC, most Facebook users do not know enough about the law to know that they are breaking it: "Neither the federal nor provincial government have invested any resources into educating the public about why we have these confidence provisions [in the Youth Criminal Justice Act.]"

Facebook itself has taken no official stand on the issue: speaking with relation to a similar case, spokesperson Simon Axten said that existing tools on the site, which allow people to report offensive content or groups, are sufficient. Those complaints, however, are handled by Facebook administrators and are judged on the basis of whether or not the site's terms of use have been violated; these administrators are unlike to have much knowledge of Canadian law and the YCJA in particular (it is legal to publish the names of accused youths in the US).

So are those Facebook users who posted the identities of the accused breaking the law? To date no charges have been laid, and after a year it seems unlikely that they will be. At the moment we seem to be in an odd situation where respected, responsible news outlets such as the Globe and Mail and Toronto Star have to abide by the law, but Internet postings do not. As seems more and more often to be the case, technology is at least one step ahead of the law.

For Classroom Discussion

- Why does the YCJA protect the identities of young offenders?

- How might it serve the interests of:

- Young accused

- Young victims

- Family of victims or accused

- Society at large

- Do you agree with these reasons?

- Why might people have chosen to reveal the identities of the victim and the accused on Facebook? Do you agree with those possible reasons?

- What powers should government have to control the publication of information online?

- Should those powers be greater within the justice system? Why or why not?

- Given that Facebook is an American company, should material it carries be subject to Canadian law? Why or why not?

- Should people be charged for posting information about young offenders or young victims on sites like Facebook? Why or why not?

Classroom Activities

- Have students research (or provide them with background on) the reasoning behind the creation of the Youth Criminal Justice Act, particularly its provisions for identity protection.

- Conduct a debate or town hall meeting on the conflict between the interests of the state and the community in keeping some information private and the right of individuals to publish or read whatever news they wish. (In the town hall meeting version, each side might have several members, representing the different interested parties: the courts, lawyers and youth advocates on the one side, for instance, and broadcasters, civil liberties advocates and Internet companies on the other. Some groups, such as friends of the accused or victim, might well have representatives on each side.)

MediaSmarts Lessons Resources

Perceptions of Youth and Crime (Grades 7-12)

What Students Need to Know about Freedom of Information and Protection of Privacy (Grades 5-10)

Free Speech Versus the Internet (Grades 10-12)