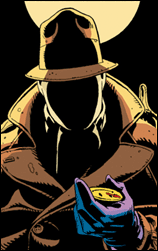

The most anticipated movie of the year, at least in some circles, is opening on March 6th: Watchmen, the adaptation of the 1986 comic book of the same name. The original, which won a Hugo Award for science fiction and was named one of Time's top 100 novels of the twentieth century, tells the story of a group of retired superheroes investigating the death of one of their colleagues; the mystery leads the reader through the alternate world their existence has created, in which heroes with cosmic superpowers overawed the Soviet Union and in which Richard Nixon is still president in 1985. Though time will tell how successful the film will turn out to be, the buzz around its launch gives an opportunity to look at comics and how they're adapted into other media.

The most anticipated movie of the year, at least in some circles, is opening on March 6th: Watchmen, the adaptation of the 1986 comic book of the same name. The original, which won a Hugo Award for science fiction and was named one of Time's top 100 novels of the twentieth century, tells the story of a group of retired superheroes investigating the death of one of their colleagues; the mystery leads the reader through the alternate world their existence has created, in which heroes with cosmic superpowers overawed the Soviet Union and in which Richard Nixon is still president in 1985. Though time will tell how successful the film will turn out to be, the buzz around its launch gives an opportunity to look at comics and how they're adapted into other media.

To begin with, it's useful to set out some of the differences between Watchmen and other adaptations of comics such as Iron Man or The Dark Knight. To begin with, the source material wasn't a long-running serial but a series of only twelve issues which told a self-contained story. (The ending of that story is fairly final, so unless great liberties have been taken there's no chance of a Watchmen 2.) The series had just one writer and artist, Alan Moore and Dave Gibbons respectively, unlike most comics which have had any number of people work on them over the years (while Iron Man was created by Stan Lee, Larry Lieber and Don Heck, for instance, the 2008 movie drew more heavily on the 1980s version by David Michelinie and Bob Layton.) Instead of the freewheeling page layouts associated with most superhero comics, almost every page of Watchmen is a rigid grid of nine panels, each stuffed with details that give verisimilitude to its fictional world and draw links between the different storylines. Finally, few of those pages feature fighting or action of any kind, most being given over instead to characters talking, dreaming, reading or just walking around.

That brief summary may explain why Watchmen, which has attracted Hollywood's attention since it was first published, has been such a challenge to adapt into film. Its writer, Alan Moore, has repeatedly said he does not think it should be made into a movie at all; while he does not own the original material, which he did as work-for-hire for DC Comics, he successfully convinced at least one prospective director to abandon the project. He's also spoken with regret about the effect Watchmen has had on the comics industry in the years since it was published, as many other writers overlooked its criticisms of the genre and instead imitated it by creating darker, grittier superheroes.

When the movie was first announced fan reaction was mixed, due both to affection for the original and Moore's opposition to any adaptation. Director Zack Snyder fended off criticisms by saying that he took the assignment because if he didn't, someone with less love for the material might ruin it. (He's certainly resisted efforts to make it more kid-friendly, letting it go to theatres with a potentially crippling R rating for sex and violence.) In an interesting example of targeted marketing, much of the promotional material released to outlets such as Wired, which cater to people familiar with the original comic, has been as much about the authenticity of the film as its quality.

Of course, one important difference between a comic and movie is that time in a comic moves at the reader's pace: there's an opportunity, if one wishes, to slow down and spot all of the details. In as dense a text as Watchmen, where repeated motifs and accompanying text pieces are key to a full understanding, the reader needs that freedom. (For instance, repeated images of watches and clockworks pun on the title – itself a reference to Juvenal's maxim “Who watches the watchmen?” – and connect to references to the Doomsday Clock, the watch-in-the-sand argument for the existence of God and Albert Einstein's comment that if he had known where his discoveries would lead he would have become a watchmaker.) A movie, though, clicks away at a relentless twenty-four frames per second, only slowing down or speeding up when the director wishes. Given that, can the movie do any more than approximate the original?

Maybe not – but perhaps that's the wrong way to look at it. Perhaps it's a mistake to imagine seeing the movie in a theatre; maybe just as the original Watchmen was a new development in the comics medium, the adaptation will be a new development in the medium of film – a movie made to be watched on DVD.

Resources

Teachers wanting to bring comics into the classroom have a wide range of resources available to them. Please note that some of these sites contain user comments that may be inappropriate for a classroom. Teachers are strongly advised to pre-select material for their classes to view and read rather than simply directing students to the sites.

Wired magazine hosts a series of short films about the making of Watchmen that cast light both on the adaptation process and film-making in general.

For the writing side, you can get examples of comic book scripts at The Comic Book Script Archive.

Teachers looking for age-appropriate comics to bring into the classroom can use this list at USA Today's Pop Candy blog.

The history of comics in Canada is covered in depth on the site Beyond the Funnies, http://www.collectionscanada.gc.ca/comics/index-e.html which ranges from 1942’s Dime Comics to Chester Brown’s recent comics biography of Louis Riel and includes history, bibliographies and sample comics. The CBC covers much the same ground with TV and radio clips on their site The Comics in Canada: An Illustrated History. http://archives.cbc.ca/arts_entertainment/visual_arts/topics/2352/

MindBlue http://popresources.pbwiki.com/Comics maintains a Wiki of comics resources that links to lesson plans, articles, resources and tools for helping students create their own comics.