Marketing and Consumerism - Special Issues for Tweens and Teens

No longer little children and not yet teens, tweens are starting to develop their sense of identity and are anxious to cultivate a sophisticated self-image. Meanwhile, marketers are discovering there’s lots of money to be made by treating tweens like teenagers. According to advertising executive Chris Vollmer, “once kids hit 12, they start having more spending power, and they even start to perceive themselves as influencers for household purchases.”[1]

By treating pre-adolescents as independent, mature consumers, marketers have been very successful in removing the gatekeepers (parents) from the picture—leaving tweens vulnerable to potentially unhealthy messages about body image, sexuality, relationships and violence.

Marketing “cool” to teens

“Teenagers have now become the gatekeepers to modern trends. With the internet and social media, teenagers have more access to that information than ever before.”[2]

(Oliver Pangborn, senior youth insights consultant at the market research firm The Futures)

Corporations capitalize on the age-old insecurities and self-doubts of teens by making them believe that to be truly cool, you need their product.

According to No Logo author Naomi Klein, in the 1990s corporations discovered that the youth market was able and willing to pay top dollar in order to be “cool.” The corporations have been chasing the elusive cool factor ever since.

Teen anger, activism and attitude have become commodities that marketers co-opt, package and then sell back to teens. It’s getting harder to tell what came first: youth culture or the marketed version of youth culture. Does the media reflect today’s teens or are today’s teens influenced by media portrayals of young people? It’s important that teens be provided with opportunities to discuss these issues and challenge the materialistic values promoted in the media.

Body image and advertising

It’s difficult for teens to develop healthy attitudes towards sexuality and body image when much of the advertising aimed at them is filled with images of impossibly thin, fit, beautiful and highly sexualized young people. The underlying marketing message is that there is a link between physical beauty and sex appeal—and popularity, success and happiness.

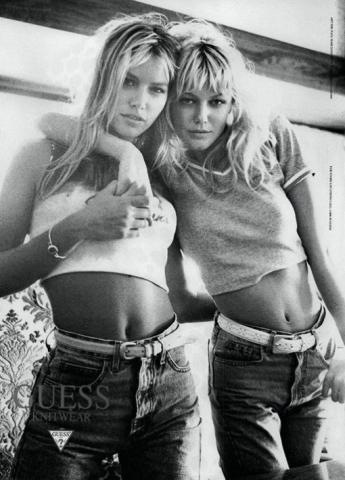

Fashion marketers such as Calvin Klein, Abercrombie & Fitch and Guess use provocative marketing campaigns featuring young models. These ads are selling more than clothing to teens—they’re also selling adult sexuality.

Media images can contribute to feelings of body-hatred and self-loathing that can fuel eating problems. While body image has long been considered a female issue, an increasing number of boys now also suffer from eating disorders. A 2012 study found that 50 percent of both boys and girls in Grade 10 felt that they were either too thin or too fat.[3] Studies have also found that boys, like girls, may turn to smoking to help them lose weight.[4]

Packaging girlhood and boyhood

As they make the transition from childhood to the teenage years, tweens (ages 8-12) are continually bombarded with limiting media stereotypes on what it is to be a girl or a boy in today’s world. This “packaged childhood” is sold to them through ads and products; and across all media, from television, music, movies and magazines to video games and the internet.

If you believe the media messages aimed at kids, tween girls are mini-fashionistas who are pretty and sexy and who are obsessed with boys, friends, shopping, pop stars and celebrities; tween boys are independent and strong, and preoccupied with sports, video games, adventure, cars, music and hanging out with friends.

Young girls in particular are targeted by marketers. The focus of these ads – beauty, sexuality, relationships, and consumerism – is worrisome for parents. According to Sharon Lamb and Lyn Mikel Brown, authors of Packaging Girlhood, images of girls as “sexy, diva, boy-crazy shoppers” can be quite harmful to their self-development. At an age when girls “could be developing skills, talents, and interests that will serve them well their whole life, they are being enticed into a dream of specialness through pop stardom and sexual objectivity.”[5]

Media stereotypes of boys are no less harmful: they are nearly always presented as “tough guys” and, as with girls, there is a consistent emphasis on their physical appearance. Ads and movies communicate a masculine ideal that is athletic and muscular. In fact, over the last twenty years action figures for properties such as Star Wars and G.I. Joe have gained more muscles than even the most dedicated body builders. Rap and hip hop videos reinforce this narrow vision of masculinity: particularly popular with youth, this musical culture – whose origins are broad and diverse – has narrowed to present a single, stereotypical image of masculinity and relations between the sexes.

Marketing adult ads to kids

The marketing of adult entertainment to children has been an ongoing issue between government regulators and various media industries. In a report released in 2000, the U.S. Federal Trade Commission (FTC) took movie, music and video games industries to task for routinely marketing violent entertainment to young children. Subsequent reports have shown that although advances have been made – particularly within the video game industry – there are still many outstanding concerns relating to the frequency that adult-oriented entertainment is marketed to children and the ease with which many youth are able to access adult-rated games, movies and music. [6] Specific areas where the FTC is calling on entertainment media to improve on include restricting the marketing of mature-rated products to children, clearly and prominently disclosing rating information and restricting children’s access to mature-rated products at retail.[7]

This is especially relevant in the emerging world of YouTube and content creators. In a 2019 statement, the FTC asked creators whether their “content is directed to children?” They then reminded creators of the Children’s Online Privacy Protection Act Rule enacted in 1998, which protects children under the age of 13 online.[8] As of 2021, however, Facebook allowed advertisers to target users as young as 13 with ads for alcohol, gambling and online dating services.[9]

The real challenge is that promotion of adult-oriented entertainment does not necessarily fall within the parameters outlined by regulatory agencies such as the FTC. For example, in 2019, Nickelodeon’s Kids Choice Awards were hosted by music producer DJ Khaled, whose songs routinely include parental advisory warning labels for material potentially unsuitable for children. The artist also came under fire in 2018 for promoting alcohol on his social media while failing to properly label them as ads, including a Snapchat featuring two bottles of alcohol poured over Cinnamon Toast Crunch.[10]

Self-commodification

One of the distinguishing features of networked media, such as social networking and video-sharing sites, is that the users provide most of the content. For many, this has led to a sense that using social media is a part of our jobs, or a job in itself: “Just like Instagram made everyone a photographer and Twitter made everyone an opinion columnist, the mere act of using social media has turned us all into creators, hustling for as many microtransactions on as many platforms as we can.”[11]

The importance of influencers in youth culture has led many young people to want to commodify themselves in the same way: six in ten teens and young adults post unpaid brand-related content and 86 percent would be willing to post sponsored content if they were paid to do it.[12] One study found that the top career aspiration for kids aged five to seven was “YouTuber.”[13]

While participating in social media can be an important form of self-expression for young people, in some cases leading to a career, it’s important for kids to understand the realities of making online media for money. YouTubers, TikTok stars, influencers and streamers all report harassment, health problems and pressure to constantly deliver new content – all of which can, of course, rob them of the enjoyment they originally took in making media.[14]

Particularly for girls, part of that is also a pressure to sexualize themselves. For would-be influencers, self-sexualization is often seen as a way or even a necessity to get attention not just from followers but from brands as well.[15] While some users are pressured to engage in literal sex work online,[16] the broader result is that social media post have developed “a fairly consistent pornified aesthetic”[17] that girls – and, increasingly, boys[18] – feel pressured to conform to.

Continue to next section

Parent resources

Teacher resources

[1] Getzler, W.G. (2015) The Power of 12: Digital Tweens Make for Marketing Sweet Spot. Kidscreen. Retrieved from https://kidscreen.com/2015/08/13/the-power-of-12-digital-tweens-make-for-marketing-sweet-spot/

[2] Lapowsky, I. (2014) Why teens are the most elusive and valuable customers in tech. INC. Marketing. Retrieved from https://www.inc.com/issie-lapowsky/inside-massive-tech-land-grab-teenagers.html

[3] Freeman et al. (2012). The Health of Canada’s Young People: A Mental Health Focus. Public Health Agency of Canada.

[4] American Journal of Health Promotion (2007). Adolescent Girls on Diets More Apt to Become Smokers.

[5] Lamb, S., & Brown, L. M. (2007). Packaging girlhood: Rescuing our daughters from marketers' schemes. St. Martin's Press.

[6] Federal Trade Commission (2009). FTC Renews Call to Entertainment Industry to Curb Marketing of Violent Entertainment to Children. https://www.ftc.gov/news-events/news/press-releases/2009/12/ftc-renews-call-entertainment-industry-curb-marketing-violent-entertainment-children.

[7] Ibid.

[8] Cohen K (2019) Youtube channel owners: Is your content directed to children? Federal Trade Commission. Retrieved from https://www.ftc.gov/news-events/blogs/business-blog/2019/11/youtube-channel-owners-your-content-directed-children

[9] Taylor, J. (2021) Facebook allows advertisers to target children interested in smoking, alcohol and weight loss. The Guardian. Retrieved from https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2021/apr/28/facebook-allows-advertisers-to-target-children-interested-in-smoking-alcohol-and-weight-loss

[10] Truth in Advertising (2018) DJ Khaled’s Snapchat Sobers Up. Truth in Advertising. Retrieved from https://truthinadvertising.org/articles/dj-khaleds-snapchat-sobers/

[11] Jennings, R. (2021) The sexfluencers. Vox. Retrieved from https://www.vox.com/the-goods/22749123/onlyfans-influencers-sex-work-instagram-pornography

[12] (2019) The Influencer Report: Engaging Gen Z and Millennials. Morning Consult.

[13] Peak, J. (2021) YouTube influencer tops job wishlist for children aged 5-7. Wigan Today. Retrieved from https://www.wigantoday.net/news/people/youtube-influencer-tops-job-wishlist-for-children-aged-5-7-3442272

[14] Needleman, S. (2021) Twitch Live-Streamers Say Playing Games is Hard Work. The Wall Street Journal.

[15] Drenten, J., Gurrieri, L., & Tyler, M. (2020). Sexualized labour in digital culture: Instagram influencers, porn chic and the monetization of attention. Gender, Work & Organization, 27(1), 41-66.

[16] Jennings, R. (2021) The sexfluencers. Vox. Retrieved from https://www.vox.com/the-goods/22749123/onlyfans-influencers-sex-work-instagram-pornography

[17] Drenten, J., Gurrieri, L., & Tyler, M. (2020). Sexualized labour in digital culture: Instagram influencers, porn chic and the monetization of attention. Gender, Work & Organization, 27(1), 41-66.

[18] Hawgood, A. (2022) What Is ‘Bigorexia’? The New York Times. Retrieved from https://www.nytimes.com/2022/03/05/style/teen-bodybuilding-bigorexia-tiktok.html