How Marketers Target Kids

As traditional forms of advertising, such as TV commercials, are becoming less effective,[2] marketers are pressed to find even more innovative and aggressive ways to cut through the “ad clutter” or “ad fatigue” of modern life. As well, the popularity of streaming services such as Netflix or Disney Plus means that today’s kids see an average of four hundred fewer hours of TV ads compared to watching commercial TV[3] – making advertisers all the more determined to reach them in other ways.

Online advertising

The internet is an especially desirable medium for marketers who want to target children. This is because:

- It’s part of youth culture. This generation of young people is growing up with the internet as a daily and routine part of their lives.

- Parents generally do not understand the extent to which kids are being marketed to online.

- Kids are often online alone, without parental supervision.

- Sophisticated technologies make it easy to collect information from young people for marketing research and to target individual children with personalized advertising.

- Even though advertising to children is monitored through the Canadian Code of Advertising Standards[4] and the Competition Act,[5] it is still allowed (except in Quebec).

- By creating engaging, interactive environments based on products and brand names, companies can easily build brand loyalties from an early age.

Ads on social media usually resemble TV or print ads or involve influencers. This may be changing, though, as newer platforms like TikTok are introducing ad formats that look more like unpaid posts. Spark Ads, a “format that allows advertisers to use organic user posts as part of their ad campaigns on the app,” is designed to take advantage of the way that products suddenly explode in popularity on TikTok. While those bursts of popularity usually happen without the help of advertising, this new format blurs the distinction between ads and posts, making it even harder for the platforms’ users to know when they’re being advertised to.[6]

Here are just a few of the different kinds of ads found on websites:

- Banner: An ad that sits at the top or the bottom of the page. More and more banner ads are persistent, which means they stay in place while you scroll up or down.

- Rail: An ad that covers the left or right margin of the site.

- Modal: An ad that covers the site’s content and has to be closed before you can see or use the site.

- Intracontent: An ad that appears between different parts of the site.

- Prevideo: A video ad that plays before you can see or use the site.

- Autoplay: A video ad that plays automatically when you visit the site.[7]

Thanks to the way we participate with content on social media, anything that people share – from GIFs[8] to memes[9] – can be an ad. Many apps aimed at young kids have ads, as well. In fact, one study of 135 kids’ apps found that every single free app contained advertising, as well as 88 percent of paid apps.[10]

Search engines

Search engines like Google, Bing and DuckDuckGo also display ads. While none of these websites let advertisers pay to influence where they come up in “organic” search results, they are often seen as an endorsement by users because paid ads appear above search results (and look the same except for an “Ad” tag).

Influencers

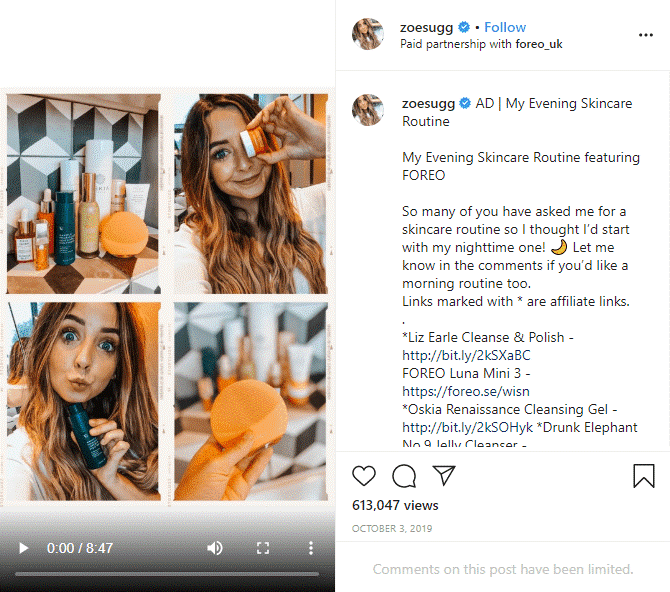

Influencers have become one of the main ways advertisers reach children and youth, and marketers take them seriously: Disney, for example, offers an eight-week course for would-be influencers on how to promote the company’s brand online.[11] While advertisers often pay influencers to promote their products, another method is to send free samples to influencers, hoping they will spread the word to their followers. Influencers, similarly, will often provide unpaid endorsements while they’re building a following in the hopes of getting free samples and, eventually, a paid endorsement deal. These promotions tend to be very successful. 50 percent of social media users prefer getting product information from influencers rather than straight from the brand themselves, and 34 percent have discovered brands from seeing an influencer’s post.[12]

While we might think that influencers mostly target teens, they do reach younger kids as well. One toy company CEO has said that “My budget for TV this year is zero. Last year I only used influencers, and this year only influencers, and I don’t see myself going back.” In fact, that company’s top toy is a kit that includes a tripod, a green screen and a selfie stick, helping kids become influencers themselves.[13] Some influencers popular with young children, like Ryan Kaji, have even come out with their own toy lines.[14]

Influencers aren’t only found on social networks: advertisers trying to target gamers, aware that they are heavy users of ad blockers, have turned to “streamers” on platforms like Twitch who get paid to display energy drinks, headphones and other products while broadcasting themselves playing video games.[15]

YouTube adopted new rules around advertising to children in 2019, which made it harder for influencers to run ads before or after their videos. YouTubers now mostly “partner” directly with a single company – which can make it even harder for kids to recognize they’re being advertised to.[16] Today, three-quarters of influencers say they make most of their money through partnerships, compared to just five percent who make it mostly from ads on their channel.[17]

Though some influencers have become world-famous, advertisers are increasingly partnering with “micro-“ or “nano-influencers” who have smaller but more devoted followings. Even more than broadly popular influencers, it’s easy to forget that nano influencers are selling something. “Nano and micro influencers can spread brand messages in a way that feels particularly authentic,” according to Jasmine Enberg of eMarketer. “Nano influencers’ followers view them as peers, and tend to trust their brand and product recommendations over those from larger influencers.”[18]

Not all influencers are paid. One particularly popular format is the “unboxing” video, in which the creator (often a child or teen) films themselves opening a package and reacting to what’s inside. While some unboxing videos are paid partnerships, many of them are done by creators hoping to land a partnership or simply to find an audience – which led Isaac Larian, the CEO of toy giant MGA Entertainment, to develop “the ultimate unboxing toy,” LOL Surprise.[19] With thousands of kids willing to make free ads, it’s not surprising that “unboxability” has become a key feature of any new toy.

Click-to-buy

More and more, social networks like Facebook, Instagram, TikTok and Snapchat are making it possible to buy what you see advertised – or what influencers are promoting – without ever leaving the app. Combined with social networks’ ability to show you targeted ads and posts based on the data they’ve collected about you, they’re able to guide your whole shopping experience, from finding a product for the first time to purchasing it.[20] Half of TikTok users say they have bought products they’ve seen advertised on the app.[21] On Snapchat it’s even possible to virtually apply lipstick through augmented reality, then buy it with a single tap if you decide it looks good.[22]

See the Online commerce section for more information on how kids buy things online.

Viral marketing

Whether it’s sharing the latest viral video on YouTube or passing around the latest cool app or game, marketers are counting on friends influencing friends to buy and/or use their products. They are also very good at pairing their products with specific individuals – and by association, their friends – on social networking sites through ad placement on home screens, newsfeeds and logout pages. Some marketers even create products specifically designed to go viral, like Starbucks’ “Unicorn Frappuccino,” for example.[23]

Even if their goal isn't to become influencers, kids can still become "brand ambassadors" on social media. Kids will often draw on their favourite brands when making videos or playing games online. Platforms like TikTok, which allow users to collaborate and remix each other's videos, also make it easier for kids to participate in the latest viral trends.

Naming rights

Corporations have turned public spaces into commodities by purchasing naming rights to arenas, theatres, parks, schools, museums and even subway systems. Cash-strapped cities see naming rights as a way to raise much-needed revenues without raising taxes.

Video games

Online games that are built around brands, products or brand-related characters – commonly known as advergames – are the perfect vehicle for building relationships between children and brands. Generally, young people don’t identify advergames as online commercials: most think they are “just games.” Fun, fast-paced and interactive, it is easy to see the huge advantage advergames have over ordinary advertisements. These immersive ads provide advertisers with what they call “sticky traffic”: users staying involved for extended periods of time.

Ads also appear in or during games, especially mobile games – either before a game, during a game or included as branded content within a game. Some ads even reward kids for watching them by giving them currency they can use to buy things in the game.[24]

Even “skins” – costumes or other items that change how a character looks – are used as ads, with advertisers offering them to players to wear like branded t-shirts. Like t-shirts, they often don’t trigger our critical sense the way more intrusive ads do: four in 10 kids wouldn’t recognize branded skins as advertising.[25]

An alarmingly high number of games aimed at pre-schoolers have advertisements that ask them to spend real money to either better their game or continue with the game altogether. These children are being manipulated, when a lot of them time they are unable to tell what is an advertisement and what is part of the game they are playing. Josh Golin, the director for the campaign for a Commercial-Free Childhood claims “it is fundamentally unfair to manipulate a young child who doesn’t know what’s happening.”[26]

Unfortunately, as Richard Freed, a child and adolescent psychologist, states, “there’s too much money to be made” to not advertise to kids. Candy Crush and Minecraft make their parent companies 2 and $2.5 billion USD a year, respectively.[27]. These in app-pop up ads may also display familiar products you’ve seen or searched for online before, having been tracked by your IP address or accepted web cookies. If a user is unwilling to pay for the “premium” version of a game, their experience will likely be flooded by advertisements for products they previously looked at online.[28]

Cross-merchandizing

A wave of media mergers has produced a handful of powerful conglomerates that now own all the major film studios, TV networks, radio and television stations, cable channels, book and magazine publishing and music companies. These giant conglomerates use their various media holdings to promote products and artists through massive cross-promotional campaigns.[29] For example, the 2018 film Black Panther was successful not only in the box office, but also in its crossover success. While promoting the film itself, Marvel also launched a social media campaign for one of its featured songs, performed by Kendrick Lamar. Marvel promoted Lamar’s song on their own pages, as well as on Lamar’s personal pages, allowing millions of consumers to access it through their social media accounts. Social media has become imperative in advertising for media and films due to its massive growth in popularity and accessibility, with celebrities able to promote their projects directly to their followers on social media platforms like Instagram.[30]

Video games often take part in cross-marketing, as well. Fortnite, one of the most popular video games, has cross-marketed with brands as diverse as the World Cup, singer Ariana Grande and Marvel, tying in with events such as the release of the 2018 film Avengers Endgame (which gave players the chance to play as both the movie’s heroes and villain).[31]

Fast food chains, such as McDonalds, use an average of 59 percent of their marketing dollars to “acquire toys, games, puzzles…to distribute with a children’s meal.”[32] Fast food restaurants also often use tie-ins with popular movies, TV shows and characters in order to attract kids and make their unhealthy foods seem more desirable or fun.

Product placement

The future of product placement as a successful advertising tool was assured after the 1982 film E.T. featured Reese’s Pieces in a pivotal scene—causing sales of the candy to jump by 65 percent. Since that time, product placement in movies, on TV, on social media and increasingly in video games has become a commonplace marketing technique that has become a specialised advertising field in its own right.

With the advent of streaming services, such as Netflix or Amazon Prime, that don’t have commercial breaks, product placement is taking on an even greater importance, as Netflix’s product placement arrangement with Coca-Cola in the series Stranger Things demonstrates.

Like many ad formats, product placement works by keeping us from noticing that it is advertising. Research has shown that advertising is less effective when we notice that we’re being advertised to. The most effective form of product placement is the kind we’re least likely to recognize as advertising: when the product or brand is mentioned by characters, but not shown.[33]

Increasingly, advertisers are moving beyond traditional product placement to “branded filmmaking,” creating episode-length or even feature-length ads. For example, outdoor clothing brand Patagonia’s documentary ÐamNation highlights the company’s environmental commitments. The line between advertising and programming has become even more blurred as commercials become TV shows: while the 2007 series Cavemen, based on the Geico ad campaign, was a famous flop, Apple TV’s Ted Lasso, based on a series of NBC sports ads, has become a critical and commercial success.[34]

Even if they don’t make an entire film, advertisers may also pay to have a particular storyline featured. For example, in an episode of the sitcom Black-ish, a character discussed Procter & Gamble’s public service campaign.[35] With the long lifespan shows now have on streaming services, a prominent storyline – like the episode of The Office in which a Staples shredder is put to a variety of absurd purposes, such as making a salad – can pay dividends for decades.

All forms of product placement are much harder to recognize and to engage with critically than traditional advertising. As Dipanjan Chatterjee of the consulting firm Forrester puts it, “If the right story has the right ingredients and it becomes worthwhile for sharing, it doesn’t come across as an intrusive bit of advertising. It feels much more like a natural part of our lives.”[36]

In kids’ media, the fusion of advertising and programming goes back for decades. Many popular series are actually created by toy companies. Whether kids are watching LEGO Ninjago on Netflix or Paw Patrol on public television, there is no question that for most shows aimed at younger kids the marketing tail wags the programming dog.[37] Kids’ shows may even be cancelled despite high ratings if toy sales aren’t high enough.[38]

Digital insert advertising

Digital insert advertising goes one step further than product placement by using computer technology to add products to scenes that were never there to begin with. This practice is common in sporting events coverage, where ads are digitally inserted onto the billboards, sideboards and playing surfaces in arenas and stadiums.

Thanks to targeted advertising, it may even be possible to add different products to the same footage based on what is known about the audience – so that a meat-eater watching a comedy might see a burger on the kitchen table while a vegan sees fruits and vegetables.[39]

While digital ads are mainly used in sports coverage, virtual advertising is starting to break into the entertainment world as producers digitally insert products into programs after the scenes are shot. The technology also allows product names to be altered in scenes, creating the potential for new advertising revenues when series are sold into syndication. For instance, in the two images below you can see where the Coca-Cola logo has been added to a Chinese TV show:

Ambient advertising

Ambient advertising refers to ads in public places. With the cost of traditional media advertising skyrocketing and an abundance of ads fighting for consumers’ attention, marketers are aggressively seeking out new advertising vehicles. Cars, bicycles, taxis and buses have become moving commercials. Ambient ads appear on store floors, at gas pumps, in washrooms stalls, on elevator walls, park benches, telephones, fruit and pressed into the sand on beaches.

Native advertising

This is an ad format that’s hard for kids and adults alike to recognize. Native ads look like the non-advertising content it appears with – an ad in a newspaper or news website that looks like a news article, for example. While these need to be identified as ads, they often use the same font and format as genuine content and research shows that these labels are ineffective at helping people tell the difference.[40] These ads are often created by the outlet where they run, “in order to resemble the seemingly objective journalism [they] imitate.”[41]

Not surprisingly, these ads are especially popular with brands and industries that want to change how the public sees them, such as fossil fuel and tobacco companies.[42]

Packaging, brands and display advertising

The ads that kids see most often are actually the old-fashioned ones: brand labels and packaging (screens – all of them – come in fourth).[43] Even more than some of the ads mentioned above, we may not always recognize things like a cereal box or a baseball cap as advertising. Just because we don’t think of them as ads, though, doesn’t mean they weren’t carefully chosen and arranged: one study of 15 randomly chosen grocery stories in Ontario found almost three thousand cereal boxes had been placed at child height, with half of those having at least one feature designed to appeal to kids.[44] Packaging is one of the only forms of advertising that is not regulated by the Ad Standards code in Canada.

Commercialization in education

School used to be a place where children were protected from the advertising and consumer messages that permeated their world, but not anymore. In fact, one study found kids see more ads at school than anywhere else.[45]

Corporations realize the power of the school environment for promoting their name and products. A school setting delivers a captive youth audience and implies the endorsement of teachers and the educational system. Schools that allow businesses to advertise are able to raise millions of dollars for the welfare of their students and teachers. Cynthia Calvert, owner of Steep Creek Media in the United States, says that over 11 years she has helped to raise millions of dollars for Texas schools. The money “has helped pay for new computers, textbooks, supplies, and so much more.”[46] David Monahan, the campaign manager for the Commercial Free Childhood company, sees it differently. He thinks kids see too much advertising as it is in their daily life and to have it in a school is wrong because “kids are in school to learn, not to help companies make money.”[47]

Marketers are eagerly exploiting this medium in a number of ways:

- Sponsored educational materials: For example, a Kraft “healthy eating” kit to teach about Canada’s Food Guide (using Kraft products) or forestry company Canfor’s primary lesson plans that make its business focus seem like environmental management rather than logging.

- Supplying schools with technology in exchange for high company visibility.

- Exclusive deals with fast food or soft drink companies to offer their products in a school or district.

- Advertising posted in classrooms, school buses, on computers, etc. in exchange for funds.

- Contests and incentive programs: For example, the Pizza Hut reading incentives program Book It! rewards children with certificates for free pizza if they achieve a monthly reading goal; or Campbell’s Labels for Education project, which provides educational resources for schools in exchange for soup labels collected by students.

- Sponsoring school events: For example, the Canadian company ShowBiz brings moveable video dance parties into schools to showcase various sponsors’ products.

- Educational games that are used or recommended by teachers: The educational game site ABCYa! includes numerous junk food ads, while the math role-playing game Prodigy displays ads for paid membership and limits what users are able to do for free (only paying members can have virtual pets, for example). As John Golin, the executive director for the Campaign for a Commercial Free Childhood, puts it, “Schools are signing up for this thinking it is free and not understanding that there’s enormous commercial pressure put on children and families when they play at home.”[48]

Continue to next section

Parent resources

Teacher resources

[1] Simpson, J (2017) Finding Brand Success in the Digital World. Forbes. Retrieved from https://www.forbes.com/sites/forbesagencycouncil/2017/08/25/finding-brand-success-in-the-digital-world/#4d6775a5626e

[2] Shapiro, B. T., Hitsch, G. J., & Tuchman, A. E. (2021). TV advertising effectiveness and profitability: Generalizable results from 288 brands. Econometrica, 89(4), 1855-1879.

[3] Vonau, M. (2019) Netflix saves our kids from up to 400h of advertisements, study finds. Android Police. Retrieved from https://www.androidpolice.com/2019/05/15/netflix-saves-our-kids-from-up-to-400h-of-advertisements-study-finds/

[4] Ad Standards. (2007) Interpreting the code: Advertising to Children. Retrieved from https://adstandards.ca/interpretation-guidelines/

[5] Szentesi, S (n.d.) Internet and new media advertising. Canadian Advertising and Marketing Law. Retrieved from http://www.canadianadvertisinglaw.com/online-advertising/

[6] Jennings, R. (2021) “TikTok made me buy it.” Vox.

[7] Nielsen, J. (2004). The most hated advertising techniques. Jakob Nielsen Alertbox (December 6, 2004).

[8] Monllos, K. (2018) That GIF You Just Shared? It Might Actually Be an Ad. Brand Knew Mag. Retrieved from https://www.brandknewmag.com/that-gif-you-just-shared-it-might-actually-be-an-ad/

[9] Ajello, T. (2021) What Memes Can Tell Us About Building Brands. AdAge. Retrieved from https://adage.com/article/opinion/what-memes-can-teach-us-about-building-brands/2359681

[10] Meyer, M., Adkins, V., Yuan, N., Weeks, H. M., Chang, Y. J., & Radesky, J. (2019). Advertising in young children's apps: A content analysis. Journal of developmental & behavioral pediatrics, 40(1), 32-39.

[11] Sloane, G. (2021) Disney Looks to Develop Rising TikTok and Instagram Creators. AdAge. Retrieved from https://adage.com/article/digital-marketing-ad-tech-news/disney-looks-develop-rising-tiktok-and-instagram-creators/2366456

[12] Gotter, A (2020) Influencer marketing in 2020. AdEspresso. Retrieved from https://adespresso.com/blog/influencer-marketing-guidelines/

[13] Verdon, J. (2021) Santa’s Top Toy Sellers This Year Are Influencers. Forbes. Retrieved from https://www.forbes.com/sites/joanverdon/2021/11/14/santas-top-toy-sellers-this-year-are-influencers/?sh=765f14291235

[14] Steele, C. (2020) Earning Millions on YouTube Is SO Easy, Children Are Doing It. PC Mag. Retrieved from https://www.pcmag.com/news/earning-millions-on-youtube-is-so-easy-children-are-doing-it

[15] Paoletta, R. (2018) How Advertisers Are Using Twitch To Reach People Who Hate Ads. Ad Exchanger. Retrieved from https://www.adexchanger.com/ad-exchange-news/how-advertisers-are-using-twitch-to-reach-people-who-hate-ads/

[16] Verdon, J. (2021) Santa’s Top Toy Sellers This Year Are Influencers. Forbes. Retrieved from https://www.forbes.com/sites/joanverdon/2021/11/14/santas-top-toy-sellers-this-year-are-influencers/?sh=765f14291235

[17] Yurieff, K. (2021) How Influencers Make Money. The Information.

[18] Wheless, E. (2021) Why Nano-Influencers are Important for Brands. AdAge. Retrieved from https://adage.com/article/digital-marketing-ad-tech-news/why-nano-influencers-are-important-brands/2366426

[19] Stratton, A. (2017) Toymakers Are Targeting Your Children Via YouTube’s Kid Influencers. Bloomberg Businessweek. https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2017-10-18/toymakers-curry-favor-with-precocious-youtube-influencers?cmpid=socialflow-twitter-businessweek

[20] Thompson, B. (2022) Digital Advertising in 2022. Stratechery. Retrieved from https://stratechery.com/2022/digital-advertising-in-2022/

[21] Hale, J. (2021) Half Of TikTok Users Buy Products They See Advertised On The Platform (Survey). TubeFilter. Retrieved from https://www.tubefilter.com/2021/05/31/tiktok-users-buy-products-advertised-ecommerce-adweek/

[22] Sloane, G. (2021) How TikTok, Instagram and Snapchat sell everything from ranch dressing to lip gloss. Ad Age. Retrieved from https://adage.com/article/media/how-tiktok-instagram-and-snapchat-sell-everything-ranch-dressing-lip-gloss/2335766

[23] Brown, R. (2017) Starbucks whips up Unicorn Frappuccino frenzy on social media. Marketing Dive. Retrieved from https://www.marketingdive.com/news/starbucks-whips-up-unicorn-frappuccino-frenzy-on-social-media/441053/

[24] (2016) We Asked 1,000 Kids What They Thought About Online Advertising. SuperAwesome.

[25] (2016) We Asked 1,000 Kids What They Thought About Online Advertising. SuperAwesome.

[26] Lieber, C (2018) Apps for preschoolers are flooded with manipulative ads, according to a new stury. Vox. Retrieved from https://www.vox.com/the-goods/2018/10/30/18044678/kids-apps-gaming-manipulative-ads-ftc

[27] Lieber, C (2018) Apps for preschoolers are flooded with manipulative ads, according to a new stury. Vox. Retrieved from https://www.vox.com/the-goods/2018/10/30/18044678/kids-apps-gaming-manipulative-ads-ftc

[28] Williams, R (2019) Google rolls out smart targeting for in-game ads. Mobile Marketer. Retrieved from https://www.mobilemarketer.com/news/google-rolls-out-smart-targeting-for-in-game-ads/550457/

[29] Tatum, M (2020) What is cross merchandizing? Wisegeek. Retrieved from https://www.wisegeek.com/what-is-cross-merchandising.htm

[30] Keller, J (2020) Get the word out: The role of social media in film marketing. INN. Retrieved from https://investingnews.com/innspired/social-media-film-marketing-promotion/

[31] Hernandez, P. (2019) Fortnite is basically a giant, endless advertisement now. Polygon. Retrieved from https://www.polygon.com/2019/5/23/18635920/fortnite-jumpman-john-wick-marvel-brand-advertisement

[32] Healthy Eating Research (2014). Food Marketing: Using toys to market childrens’ meals. Retrieved from https://healthyeatingresearch.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/07/her_marketing_toys_AUGUST_14.pdf

[33] Fossen, B. L., & Schweidel, D. A. (2019). Measuring the impact of product placement with brand-related social media conversations and website traffic. Marketing Science, 38(3), 481-499.

[34] Sperling, N., & Hsu T. (2021) With Fewer Ads on Streaming, Brands Make More Movies The New York Times. Retrieved from https://www.nytimes.com/2021/03/23/business/media/branded-content-movies.html

[35] Sweney, M. (2018) Forget product placement: now advertisers can buy storylines. The Guardian. Retrieved from https://www.theguardian.com/media/2018/jan/20/forget-product-placement-advertisers-buy-storylines-tv-blackish

[36] Sperling, N., & Hsu T. (2021) With Fewer Ads on Streaming, Brands Make More Movies The New York Times. Retrieved from https://www.nytimes.com/2021/03/23/business/media/branded-content-movies.html

[37] Fetters, A. (2020) Toy Commercials Are Being Replaced by Something More Nefarious. The Atlantic. Retrieved from https://www.theatlantic.com/family/archive/2020/02/how-toys-are-marketed-kids-without-cable-tv/605920/

[38] Campbell, A. J. (2016). Rethinking Children's Advertising Policies for the Digital Age. Loy. Consumer L. Rev., 29, 1.

[39] (2020) Advertisers can digitally add product placements in TV and movies – tailored to your digital footprint. The Current. Retrieved from https://www.cbc.ca/radio/thecurrent/the-current-for-jan-31-2020-1.5447280/advertisers-can-digitally-add-product-placements-in-tv-and-movies-tailored-to-your-digital-footprint-1.5447284

[40] Wojdynski, B. W., & Evans, N. J. (2016). Going native: Effects of disclosure position and language on the recognition and evaluation of online native advertising. Journal of Advertising, 45(2), 157-168.

[41] Amazeen, M. (2022) Researchers looked at nearly 3,000 native ads across five years. Here’s what they found. NiemanLab. Retrieved from https://www.niemanlab.org/2022/02/researchers-looked-at-nearly-3000-native-ads-across-five-years-heres-what-they-found/

[42] Amazeen, M. (2022) Researchers looked at nearly 3,000 native ads across five years. Here’s what they found. NiemanLab. Retrieved from https://www.niemanlab.org/2022/02/researchers-looked-at-nearly-3000-native-ads-across-five-years-heres-what-they-found/

[43] Watkins, L., Gage, R., Smith, M., McKerchar, C., Aitken, R., & Signal, L. (2022). An objective assessment of children's exposure to brand marketing in New Zealand (Kids' Cam): a cross-sectional study. The Lancet Planetary Health.

[44] Rachel, P. (2017). Food marketing to children in Canada: a settings-based scoping review on exposure, power and impact. Health promotion and chronic disease prevention in Canada: research, policy and practice, 37(9), 274.

[45] Watkins, L., Gage, R., Smith, M., McKerchar, C., Aitken, R., & Signal, L. (2022). An objective assessment of children's exposure to brand marketing in New Zealand (Kids' Cam): a cross-sectional study. The Lancet Planetary Health.

[46] (2018) Should kids see Ads at school? Junior Scholastic. Retrieved from https://web.archive.org/web/20221001224956/https://junior.scholastic.com/issues/2018-19/100818/should-kids-see-ads-at-school.html

[47] Ibid.

[48] Solon, O. (2021) Child protection nonprofit alleges ‘manipulative’ upselling with math game Prodigy. NBC News. Retrieved from https://www.nbcnews.com/tech/tech-news/child-protection-nonprofit-alleges-manipulative-upselling-math-game-prodigy-n1258294