Online Commerce

Shopping online

Young people have more and more ways to buy things online, not just through e-commerce sites like Amazon, but through app stores, video games and even social network apps. Here are some essential things that parents and kids need to know about.

In-app purchases

Many popular games and apps have a freemium or free-to-play model, which means the basic version is free but you either have to pay to access the full content or you are encouraged to buy extras such as filters and costumes. Many of these features are also aggressively advertised within the games.[1]

These are most often found in commercial games but also occur in educational games such as Prodigy.

Here are some ways that games and apps encourage kids to spend money:

- Competition: Users may buy in-app purchases either to literally compete with others (such as buying exclusive weapons in a game) or for social competition (having a custom “skin,” for instance, or using the same photo filter as all of your friends).[2]

- In-game currency: In many games and platforms, you can’t buy things directly with real money but instead have to buy a virtual currency. The game platform Roblox, for example, requires users to buy “Robux” to buy anything within any of its games. In-game currency usually has to be bought in round amounts, so there is often a certain amount left over – which encourages you to get more so that you can buy something else.

- Parasocial interaction: As with endorsements, influencers and branded characters, parasocial interaction – believing that someone you know through media is really your friend – can influence in-game purchases. Games and apps such as Barbie Magical Fashion and Strawberry Shortcake Bake Shop have their characters encourage users to buy items or upgrade to the paid version.[3]

- Pay-to-skip: Some games make it more difficult or time-consuming to play without buying an in-app purchase. They will often encourage you to spend money to avoid doing a boring, repetitive job (“grinding”) or set artificial limits to how often you can do something.[4]

- Randomization: One of the most popular kinds of in-app purchase is “loot boxes,” which contain random items that are only revealed after you’ve bought them.[5] Even though players find it frustrating, they spend more on loot boxes than they would to buy the same item from an open marketplace.[6] Sometimes games make the experience even more like gambling by showing a spinning wheel or slot-machine like animation before the contents of the box are revealed, often ending with a “near miss” that suggests the player almost won the most desired prize.[7]

- Social interaction: In some games, features that let you interact with other players are only available with a paid account or in-app purchases, or limit how many friends you can have in the game unless you pay to be able to add more.[8]

- Unlocking content: Having to pay to access some part of the gameplay or requiring a membership to access some features, like a pet or house in the game world.[9]

It’s essential that kids understand how in-app purchases work and how a game or app may try to manipulate them, especially since they often don’t realize they’re spending real money or have trouble keeping track of how much they’ve spent.[10]

Dark patterns

Commercial environments have always been designed to make us spend as much money as possible: grocery stores stack children’s cereal at kid-height, hide low-cost essentials so that you have to pass by higher-margin items to get to them and put impulse buys near the cash register.

Because digital media experiences are shaped by the tools we use, this is nothing compared to the ways that an online platform like an app or website can manipulate you. Many use what are called “dark patterns” to get you to click on ads, buy things, pay more, collect your personal information or even use you as a spokesperson.[11]

Here are some of the most common dark patterns:

- Added friction: Making it harder to do the things they don’t want you to do, such as adding an “Are you sure?" button when you try to leave an app or website or to cancel a membership or subscription. Apps and games may also try to reduce friction for things they want you to do, such as giving credit card information when you first sign up so that you don’t have to enter it every time you buy something.

- Bait-and-switch: Having a button or other tool that does something other than what users expect, like a “Find out more” button that actually sends you to a signup page.

- Confusing language: Phrasing an action so that you’re not sure what’s going to happen.

Image

- Decision up front: Making the user decide to do something – like create an account or agree to a privacy policy – in order to be able to use the site or service.

- Dynamic pricing: Changing the price of an item to make you pay as much as possible. This might be based on the time of day (prices are usually higher in the morning, when more people are shopping) or on what the site knows about you (whether you’re using a PC or a Mac, for instance, or whether your browsing history suggests you’re a more budget-conscious or luxury-minded consumer).

- Fake bandwagon or fake scarcity: Falsely making it look as though an item is almost sold out or is about to become unavailable, or making you feel pressured by saying that a certain number of people are looking at the same item. Virtual items may be made artificially scarce by having a limited number available or making them on sale for a limited time.

- Friend spam: Getting access to your contact list or social network account and then sending marketing messages to your friends.

- Emotional manipulation: Having onscreen characters encourage a particular choice or say they’re sad if the user doesn’t do something (such as buying in-app purchases).

- Hidden costs: Hiding costs like shipping and handling until the very last moment.

- Hidden opt-out: Making it as hard as possible to find the way of opting out of something, such as putting an opt-out box for data sharing deep within a lengthy terms of service document.

- Limiting choices: Making it hard for users to do a particular thing (such as giving only “OK” and “Not Now” as options, so that the user has to re-confirm their choice later).

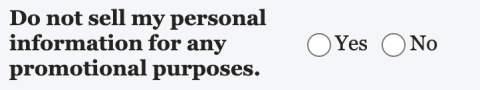

-

- Misleading graphics: Using elements like colour or layout to nudge the user towards a particular action, such as by colouring the choices they don’t want you to choose grey (making it look disabled) or making the buttons they do want you to click bright blue. One mobile ad even made it look like a hair was on the screen so users would tap the ad when they tried to brush the hair off!

- Opt-in by default: Making it seem as though you have to opt into buying or choosing something, when in fact you have to opt out.

- Self-preferencing: E-commerce sites like Amazon sell their own brands alongside products from other companies. It’s not always obvious that these are house brands, but they usually rank much higher in search results and recommendations than other brands. Amazon brands, for instance, make up half of the non-sponsored search results for most product types, even though they make up just six percent of the available products, with brands such as Happy Belly Cinnamon Crunch appearing above much better-known and better-rated competitors.[12]

Buy now, pay later

Social media influencers don’t just promote products: in many cases, they also endorse “buy now, pay later” or point-of-sale loans as a way of buying their latest fabulous outfit. With these services, buyers make only a partial payment right away and then pay the rest in monthly or biweekly installments. Point-of-sale loan companies don’t generally do credit checks before approving a loan, which means that young people – who typically have little experience managing their own finances – can easily accumulate large amounts of debt.

While still a much smaller industry than credit cards, point-of-sale loans are growing: more than $20 billion dollars in purchases were made with them in the US in 2021. There is reason to worry, though, that “coupling nearly instantaneous loans with an influencer-addled social media culture that prioritizes exorbitant spending and normalizes debt could be further jeopardizing the financial futures of young people through just four easy payments.”[13]

Continue to next section

Parent resources

Teacher resources

[1] Petrovskaya, E., & Zendle, D. (2021). Predatory Monetisation? A Categorisation of Unfair, Misleading and Aggressive Monetisation Techniques in Digital Games from the Player Perspective. Journal of Business Ethics, 1-17.

[2] Hamari, J., Alha, K., Järvelä, S., Kivikangas, J. M., Koivisto, J., & Paavilainen, J. (2017). Why do players buy in-game content? An empirical study on concrete purchase motivations. Computers in Human Behavior, 68, 538-546.

[3] Meyer, M., Adkins, V., Yuan, N., Weeks, H. M., Chang, Y. J., & Radesky, J. (2019). Advertising in young children's apps: A content analysis. Journal of developmental & behavioral pediatrics, 40(1), 32-39.

[4] Hamari, J., Alha, K., Järvelä, S., Kivikangas, J. M., Koivisto, J., & Paavilainen, J. (2017). Why do players buy in-game content? An empirical study on concrete purchase motivations. Computers in Human Behavior, 68, 538-546.

[5] Ball, C., & Fordham, J. (2018, July). Monetization is the message: A historical examination of video game microtransactions. In DiGRA’18–abstract proceedings of the 2018 DiGRA international conference: The game is the message (pp. 25-28).

[6] Diaczok, M. P., & Tronier, P. An investigation of monetization strategies in aaa video games.

[7] Cobb, C. (2017) Video Game Monetization Strategies. Game Developer. Retrieved from https://www.gamedeveloper.com/business/video-game-monetization-strategies

[8] Hamari, J., Alha, K., Järvelä, S., Kivikangas, J. M., Koivisto, J., & Paavilainen, J. (2017). Why do players buy in-game content? An empirical study on concrete purchase motivations. Computers in Human Behavior, 68, 538-546.

[9] Hamari, J., Alha, K., Järvelä, S., Kivikangas, J. M., Koivisto, J., & Paavilainen, J. (2017). Why do players buy in-game content? An empirical study on concrete purchase motivations. Computers in Human Behavior, 68, 538-546.

[10] Lupiáñez-Villanueva, F., Gaskell, G., Veltri, G. A., Theben, A., Folkvord, F., Bonatti, L., ... & Codagnone, C. (2016). Study on the impact of marketing through social media, online games and mobile applications on children's behaviour.

[11] Narayanan, A., Mathur, A., Chetty, M., & Kshirsagar, M. (2020). Dark Patterns: Past, Present, and Future: The evolution of tricky user interfaces. Queue, 18(2), 67-92.

[12] Jeffries, A., & Yin L. (2021) Amazon Puts Its Own Brands First Above Better Rated Products. The Markup. Retrieved from https://themarkup.org/amazons-advantage/2021/10/14/amazon-puts-its-own-brands-first-above-better-rated-products

[13] Bote, J. (2022) “'Buy now, pay later' is sending the TikTok generation spiraling into debt, popularized by San Francisco tech firms.” SFGate. Retrieved from https://www.sfgate.com/news/article/influencers-lead-Gen-Z-into-debt-17142294.php