Advertising techniques

Here are some of the most common techniques that advertisers use to get us to remember, like and buy their products.

Ad appeals

The most easily recognizable ad techniques are those that provide a “reason why” to buy a product or to prefer one product over another.[3]

Quality

The most basic “reason why” claim is that the product is good: the car is fast, the chocolate bar is tasty, the battery lasts a long time and so on. These appeals are most common in ads aimed at kids (who are still developing their brand preferences) in ads for new products or in ads for low-cost products.

Here are some ways that advertisers can send a misleading message about quality:

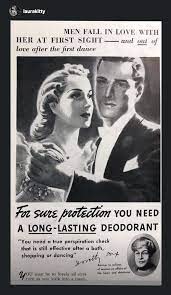

- Create the problem, sell the solution: These ads work by making you afraid or worried about something, then presenting the product as a solution. Sometimes these “activate” a fear or anxiety we already have, like bad breath; sometimes they create anxieties that didn’t even exist before. The first antiperspirants were marketed to surgeons and craftspeople as a way of keeping their hands dry, but it was only when ads suggested that underarm odour could spoil a woman’s chance at marriage that they became successful.[4] (See “Emotional appeals” below for more on how they do this.)

- Tell a story: If advertisers don’t have a specific quality claim to make about their product, they can tell a story that shows it instead. For example, an ad could show how a product would be useful in a particular situation without saying anything outright about its quality.

- Weasel words: These let advertisers seem to be making a claim without actually making one.

- Classic weasel words include “improved,” “premium” and “natural,” all of which sound good but don’t actually mean anything.

- Words like “crunchy” or “juicy” make a product sound good but can’t be proven or disproven (how do you measure crunchiness?).

- Saying that a product “fights” something or “helps” to do something only means that it affects those things in some way.

- Some ads will also use weasel phrases, as well. A sugary cereal can be “part of a balanced breakfast” (if you have it with milk, fruit, and peanut butter bread) while a gum could stop bad breath for “up to” six hours (or possibly a lot less).

Value

Another one of the most basic claims is that a product is a good value for the money. About a third of consumers are mostly motivated by price and value.[5]

There are ways, however, that advertisers can make a price seem more attractive without actually giving you a better bargain:[6]

- Add a higher-cost option: When there’s more than one option, we look at prices in relation to each other. Adding an option that costs more makes all of the other prices look lower.

- Confuse the buyer: Adding a lot of choices can nudge buyers into taking the simplest option. If you have a dozen choices to make at a fast food restaurant, it’s tempting to just go with a “value meal” instead of doing the math to figure out if it’s really Even high-end products use this appeal sometimes: although Apple products are more expensive than their competitors, part of their sales pitch is that they’re easier to use and that you have fewer choices to make when buying one.

- Give less value for the same product: Marketers know that we hate it when things we buy get more expensive. Rather than raise prices, they often cut the cost by doing something like making the product smaller or switching to a cheaper kind of packaging.

- Leave out the shipping and handling and the tax: The original price is likely to stick in our minds, and by the time we’re ready to buy we’re unlikely to change our minds – especially when we’re shopping online.

- Show prices in small text: It may be hard to believe, but we instinctively think a price in smaller text is lower!

For low-cost items:

- Keep the first number as low as possible: When we’re making a small purchase, like groceries, we mostly just pay attention to the first number. So even though $5.99 is just a penny less than $6.00, we see it as being a lot cheaper.

- Show the price before the product, because we are more likely to be value-minded when shopping for low-cost items.

But for high-cost items:

- Be as specific as possible: At high price points, very specific numbers like $2,978 seem more “honest” than rounded numbers like $2900.

- Show the product before the price, to give us time to think about how much we want it before we find out how much it costs.

Endorsement

One of the oldest and most effective ad appeals is an endorsement from someone the customer likes and respects. While historically endorsements have mostly come from musicians, actors and athletes, today endorsements from social media “influencers” are priceless for reaching kids.[7]

These ads work through what is called a parasocial relationship between the endorser and the customer. This is when we feel like we know somebody we have never met, but whom we have seen in media – even if they’re a fictional character, like a comic book superhero or a cereal mascot.[8] While it is possible to form a parasocial relationship through traditional media,[9] the interactive nature of social networks and other digital platforms makes them “more organic, intimate, and integrated into our everyday lives, in no small part because our ‘real’ relationships are already increasingly virtual.”[10]

Children and teens are particularly likely to form parasocial relationships.[11] When kids have a positive “relationship” with an endorser, they are more likely to feel loyal to a brand.[12] Kids who see influencers promoting junk food are more likely to eat unhealthy snacks.[13]

Health claims and health halos

Some products make health-related claims, highlighting the nutrients in food or the benefits of a device like a fitness tracker. These can be misleading in different ways. Ads or packaging may say that a product doesn’t have something (“fat free”) without making a claim that it is healthful overall, or make a claim that doesn’t make a difference to most customers’ health like pointing out that potato chips are “gluten free.”

Health claims don’t just give us information, though: they give the product a “health halo” that makes us feel like they’re good for us in general. Orange juice, for example, has often been marketed with a health appeal that hides the fact that it is basically a soft drink with vitamins added.[14] In fact, one study found that most products that make health claims are high in fat, salt or sugar.[15] Health halos don’t come just from nutritional claims, though. Images of fruit, brown paper packaging, “natural” colours or even a “shapely” bottle can make us think an item is healthful.[16] Some brands are built entirely around giving a health halo to junk food, such as Peatos (Cheetos made from peas) that are overall no more healthful than their corner-store equivalents.[17]

Other ad techniques

While it’s fairly easy to help kids recognize “reason why” ads, it can be harder for them to see the persuasive intent of ads that don’t make a specific claim about the thing being advertised. It’s important to make sure they understand many ads have other purposes and teach them to recognize the ways marketers achieve those purposes.

Emotional appeals

One of the most common ways that ads influence without making a specific claim is through how they make us feel. The best-known kind of emotional marketing is the “feel good ad,” such as the classic “I’d Like to Buy the World a Coke” campaign, which uses music and images to evoke a positive emotion and associate it with the product. Emotional appeals are more effective when they evoke more specific emotions and when the prospective buyer has limited time to make a decision.[18]

But ads don’t have to make us feel good to influence us. In fact, any of the “activating” emotions – such as fear, anger and even disgust, as well as joy – can trigger a reaction that’s useful to advertisers.[19]

It’s important, though, that the emotion is triggered at the right time: “the key to creating strong memories in consumers in a commercial or marketing campaign [is] to show the brand or the product being sold at the precise moment when our emotions were running high.”[20] With digital ads, it’s even possible to match an appeal to the emotion a viewer is (probably) already feeling.[21]

Emotional appeal techniques

- Colour: One of the most basic but significant parts of almost any ad is colour.[22] Bright, vivid colours can make a product seem more memorable and exciting,[23] while brown or other dull colours can make it seem healthful or environmentally friendly.

- Feel-good ads: These build positive feelings about a brand or product by connecting it with things that make you feel good or feel good about yourself. An ad for a restaurant might show a family or a group of friends all having fun together, while an ad for dog food might show a dog running happily to greet its owner.

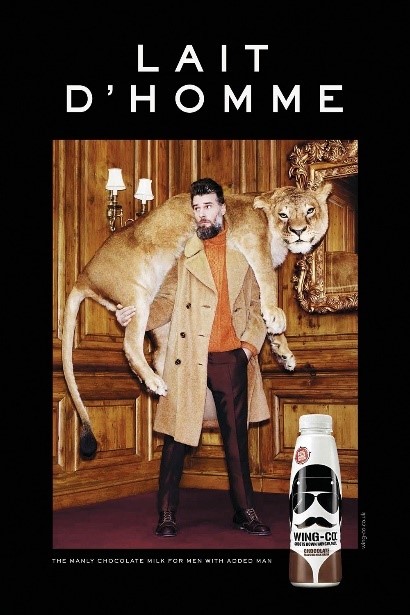

- “Anti-ads” or “anti-brands” get your attention and flatter your intelligence by telling you that you’re too smart to fall for advertising. The most famous example in Canada is the “No Name” brand that uses plain black and yellow packaging on all its products. This technique lets advertisers “have their cake and eat it too.” This ad for “Lait D’Homme” makes fun of how masculinity is used in advertising, but still uses it to sell a product that might be seen as unmanly (chocolate milk).

- “Cause advertising”: People see ads that talk about values instead of products as more trustworthy.[24] This is a kind of feel-good ad that can be very effective for building positive feelings, as well as other activating emotions. For example, taking a stand against something that consumers consider unjust can evoke anger, while suggesting that buying the product can improve something important can make people feel hope.

In some cases, a brand can get so strongly connected to a cause that buying it becomes part of people’s political identity (see “Selling identity” below.)

- It’s important to teach kids to make sure that companies “walk the walk” and don’t engage in practices like greenwashing (falsely claiming environmental benefits or highlighting positive action while hiding other negative impacts).

- Some cause ads only mention the brand, not the product, like Dove’s “Campaign for Real Beauty” or Bell’s “Let’s Talk” campaign. While these campaigns can do good, kids need to understand that they are still ads for the brand.

- Humour: Making an ad that’s funny is a way to make it memorable, to have it go viral and to make us connect the brand or product with good feelings.

- Music: One of the most important tools in advertisers’ toolbox is music. Whether it’s an old pop song that makes us nostalgic for our youth, a jingle that we can’t get out of our heads or sappy strings that make us cry even when we know we’re being manipulated, music has a powerful emotional effect on us.

- Variety: Besides value for money and brand loyalty, the third most common way people decide what to buy is because they want variety. This explains the endless parade of new potato chip and soft drink flavours, new gadgets on razors, and other “new” and “improved” features that have led the average supermarket to have five times as many different items today than in 1980.[25]

- Marketers have to be careful, though, because if there are too many options, buyers will often take the simplest choice (see “Ad appeals” above). That’s why they often stop production of old varieties when adding new ones, creating the impression of more variety without giving the buyer too many choices.

Building brand awareness and loyalty

Ads that are focused on the brand, instead of the product, have two goals: to make customers aware of the brand and to make customers loyal to that brand.

Brands have a powerful impact on us. Participants in one taste test between Coca-Cola and another cola overwhelmingly chose Coke. Only after the test was over were they told that the inferior mystery cola was also Coca-Cola, but without all of the imagery, commercials, music and experiences that were tied to its logo and distinctive bottle.[26]

While branding had been part of advertising since its early days, Canadian author Naomi Klein identified a shift towards brand-building as the primary form of advertising in her 2000 book No Logo. According to Klein, the mid-1980s saw the birth of a new kind of corporation—Nike, Calvin Klein and Tommy Hilfiger, to name a few—which changed their primary corporate focus from producing products to creating an image for their brand.[27]

Marketers plant the seeds of brand recognition in very young children in the hopes that the seeds will grow into lifetime relationships. Babies as young as six months of age can form mental images of corporate logos and mascots. Brand loyalties can be established as early as age two, and by the time children head off to school most can recognize hundreds of brand logos.[28] Those efforts are rewarded by strong brand loyalty: by the time young teens are able to spend their own money, more that half of it goes to their favourite brands.[29]

Online games that are built around brands, products or brand-related characters – commonly known as advergames – are the perfect vehicle for building relationships between children and brands. Generally, young people don’t identify advergames as online commercials: most think they are “just games.” Fun, fast-paced and interactive, it is easy to see the huge advantage advergames have over ordinary advertisements. These immersive ads provide advertisers with what they call “sticky traffic”: users staying involved for extended periods of time.

While fast food, toy and clothing companies have been cultivating brand recognition in children for years, adult-oriented businesses such as banks and automakers are now getting in on the act. Branding is especially important in categories where there is little actual difference between competing products.[30]

Brand mascots

One kind of brand-building that is especially common in ads aimed at kids is the brand mascot. Memorable, appealing characters like Tony the Tiger can create a parasocial relationship, building positive feelings about a brand that last into adulthood. In fact, one study found that parents were more likely to see a cereal as being healthful if it featured a mascot they recognized from childhood.[31] Using characters from other media can also be an effective way of getting kids interested in a product.

Differentiation

Another use of branding is to let marketers target their ads more specifically. Sometimes this can be as simple as having separate pink and blue brands of razors, but may also be based on more complex aspects of our self-image.

Brands aimed at kids will often try to differentiate their brands as being exclusively for kids and not for adults. Teenagers, for example, may be drawn to “content that means absolutely nothing to the adults around them; the funniest and best content is the content that only they understand.”[32]

Selling identity

One of the most effective forms of advertising is selling an identity through the brand. Teens, who are still developing their identities and are very sensitive how their peers see them, are especially vulnerable to this.[33]

Sometimes selling identity is about how you want other people to see you: the Toyota Prius outsold other hybrid cars partly because its appearance stood out from regular cars, so that owning one sent a stronger message of concern for the environment.[34] Similarly, luxury brands like Apple are able to charge higher prices because they are a recognizable sign to other people that you can afford to buy them.

Other times, buying identity is about how you want to see yourself. Ads that feature popular or good-looking people both trigger insecurity (see “Emotional appeals” above) and sell the fantasy that buying the product can make us like them. Even some ads that look like they’re making a value claim are actually identity ads: a commercial that highlights a sport utility vehicle’s ability to go offroad, for instance, is aimed more at people who want to think they’ll take it offroad than to people who actually do go offroad.

Some ads also appeal to an identity people already have. This may be very specific, such as using hockey to appeal to Canadians, but more often it involves appealing to a broad personality type or a political identity.

Sometimes it’s important for a brand to help you preserve your identity. In the 1950s, many women were reluctant to use instant cake mixes because it seemed too easy: they didn’t feel like they were doing their jobs as mothers. The Betty Crocker brand solved this problem by encouraging women to treat baking the cake as just one part of the process, publishing ads and even cookbooks that featured cakes with elaborate icing and decorations.[35] More recently, products traditionally marketed mostly to women, like soap, have introduced “masculine” versions to target men who might otherwise be reluctant to buy them.

Repeat business and reassurance

Some ads can be effective even after you’ve bought the thing being advertised. Seeing an ad for something that you’ve recently bought can be a way of turning a one-time purchase into a lifelong brand loyalty. With expensive items, seeing an ad can provide people who’ve bought something “reassurance that they made the right decision. The ad acts as a balm for that slight post-spend dip in enthusiasm, ultimately arming them as roving emissaries for the product.”[36]

Continue to next section

Parent resources

Teacher resources

[1] Kunkel, D. (2010). Commentary: Mismeasurement of children's understanding of the persuasive intent of advertising.

[2] Stanley, S. L., & Lawson, C. A. (2018). Developing discerning consumers: an intervention to increase skepticism toward advertisements in 4-to 5-year-olds in the US. Journal of Children and Media, 12(2), 211-225.

[3] O'Reilly, T. E., & Tennant, M. (2009). The age of persuasion: How marketing ate our culture. ReadHowYouWant. com.

[4] Peck, E. (2012) How Advertisers Convinced Americans They Smelled Bad. Smithsonian Magazine.

[5] Moss, M. (2021). Hooked: food, free will, and how the food giants exploit our addictions. Random House.

[6] Kolenda, N. (n.d.) Psychology of Pricing.

[7] Gotter, A (2020) Influencer marketing in 2020. AdEspresso. Retrieved from https://adespresso.com/blog/influencer-marketing-guidelines/

[8] Brunick, K. L., Putnam, M. M., McGarry, L. E., Richards, M. N., & Calvert, S. L. (2016). Children’s future parasocial relationships with media characters: The age of intelligent characters. Journal of Children and Media, 10(2), 181-190.

[9] Horton, D., & Richard Wohl, R. (1956). Mass communication and para-social interaction: Observations on intimacy at a distance. psychiatry, 19(3), 215-229.

[10] Adegbuyi, F. (2021) The Blurred Lines of Parasocial Relationships. Cybernaut. Retrieved from https://every.to/cybernaut/the-blurred-lines-of-parasocial-relationships

[11] Brunick, K. L., Putnam, M. M., McGarry, L. E., Richards, M. N., & Calvert, S. L. (2016). Children’s future parasocial relationships with media characters: The age of intelligent characters. Journal of Children and Media, 10(2), 181-190.

[12] Chung, S., & Cho, H. (2017). Fostering parasocial relationships with celebrities on social media: Implications for celebrity endorsement. Psychology & Marketing, 34(4), 481-495.

[13] Coates, A. E., Hardman, C. A., Halford, J. C., Christiansen, P., & Boyland, E. J. (2019). Social media influencer marketing and children’s food intake: a randomized trial. Pediatrics, 143(4).

[14] Braun, A. (2014) Misunderstanding Orange Juice as a Health Drink. The Atlantic. Retrieved from https://www.theatlantic.com/health/archive/2014/02/misunderstanding-orange-juice-as-a-health-drink/283579/

[15] Siddique, H. (2021) More than half of snacks marketed as healthy are high in fat, salt or sugar. The Guardian. Retrieved from https://www.theguardian.com/food/2021/mar/09/snacks-marketed-as-healthy-high-in-fat-salt-sugar

[16] Krieger, E. (2019) How food companies use packaging to fool you into thinking an item is healthful. The Washington Post.

[17] Chaker, A.M. (2019) The Junk Food That Wants to Have It Both Ways. The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved from https://www.wsj.com/articles/the-junk-food-that-wants-to-have-it-both-ways-11571847252

[18] Kolenda, N. (n.d.) The Psychology of Emotions in Advertising.

[19] McDuff, D., & Berger, J. (2020). Why do some advertisements get shared more than others?: Quantifying facial expressions to gain new insights. Journal of Advertising Research, 60(4), 370-380.

[20] Moss, M. (2021). Hooked: food, free will, and how the food giants exploit our addictions. Random House.

[21] Kolenda, N. (n.d.) The Psychology of Emotions in Advertising.

[22] Milosavljevic, M., & Cerf, M. (2008). First attention then intention: Insights from computational neuroscience of vision. International Journal of advertising, 27(3), 381-398.

[23] Moss, M. (2021). Hooked: food, free will, and how the food giants exploit our addictions. Random House.

[24] Bowler, H. (2021) People trust ads that talk about values, not products, finds Nielsen. The Drum. Retrieved from https://www.thedrum.com/news/2021/12/13/people-trust-ads-talk-about-values-not-products-finds-nielsen

[25] Moss, M. (2021). Hooked: food, free will, and how the food giants exploit our addictions. Random House.

[26] O'Reilly, T. E., & Tennant, M. (2009). The age of persuasion: How marketing ate our culture. ReadHowYouWant. com.

[27] Klein, N. (2000) No Logo. Penguin Random House.

[28] Kinsky, E. S., & Bichard, S. (2011). “Mom! I've seen that on a commercial!” US preschoolers' recognition of brand logos. Young Consumers.

[29] (2021) Young Teens Are Different: How to Effectively Reach the Influential 13-16 Market. SuperAwesome. Retrieved from https://www.superawesome.com/young-teens-are-different-report/

[30] O'Reilly, T. E., & Tennant, M. (2009). The age of persuasion: How marketing ate our culture. ReadHowYouWant. com.

[31] Krashinsky, S. (2014) The effects of ads that target kids shown to linger into adulthood. The Globe and Mail. Retrieved from https://www.theglobeandmail.com/report-on-business/industry-news/marketing/lovable-marketing-icons-retain-their-power-into-adulthood/article17479332/

[32] (2021) Young Teens Are Different: How to Effectively Reach the Influential 13-16 Market. SuperAwesome. Retrieved from https://www.superawesome.com/young-teens-are-different-report/

[33] Pechmann, C., Levine, L., Loughlin, S., & Leslie, F. (2005). Impulsive and self-conscious: Adolescents' vulnerability to advertising and promotion. Journal of Public Policy & Marketing, 24(2), 202-221.

[34] Champniss, G., et al. (2015) Why Your Customers’ Social Identities Matter. Harvard Business Review. Retrieved from https://hbr.org/2015/01/why-your-customers-social-identities-matter

[35] Mikkelson, D. (2008) Requiring an egg made instant cake mixes sell? Snopes. Retrieved from https://www.snopes.com/fact-check/something-eggstra/

[36] O'Reilly, T. E., & Tennant, M. (2009). The age of persuasion: How marketing ate our culture. ReadHowYouWant.com.