Body image – Digital media

Video games

One feature common to most video games and all virtual worlds is an avatar, a character that represents the player within the world. In nearly all worlds the appearance of these avatars can be customized (though often this is only possible for paying users, while those who use the free version are stuck with the “default” versions). Unfortunately, players can be just as insecure about their virtual bodies as they are about their real ones, as realistically-depicted female characters in video games are highly sexualized and “thinner than the average American,”[1] while male avatar body types are generally larger and more muscular.[2] In fact, boys encounter such heavily muscled characters that six- to ten-year-old boys who read gaming magazines for a year reported greater body dissatisfaction than those who read fashion, sports or fitness magazines.[3]

While games appealing to the youngest children, such as Roblox and Minecraft, have either non-human or extremely cartoony avatars, those aimed at slightly older children typically provide a narrow range of avatar options which reinforces cultural values of attractiveness. As academic Sara Grimes put it in her essay “I’m a Barbie Girl, in a BarbieGirls World,” “most avatars end up looking eerily alike – thin, youthful females… with large heads and delicate facial features.”[4]

Even in virtual worlds where avatars are fully customizable, such as The Sims, research has shown that players make their avatars fit mainstream standards of attractiveness. Author Connie Morrison was astounded to discover that there were no “fat avatars” and concluded that messages given in virtual worlds, such as The Sims or Fortnite, are that players should choose what society deems ideal bodies.[5]

People respond to physical characteristics in avatars just as they do in real life – seeing taller, more attractive avatars as being more likeable or persuasive, for example – and will even change their behaviour based on their avatar’s appearance, becoming more confident and sociable if their avatar is made more attractive. This is known as the Proteus effect, which is when “the behaviour of an individual conforms to [their] digital self-representation.”[6] This effect underlines the potential of avatar creation for behavioural modeling, as people who are overweight can be motivated to exercise and change their diet.[7] This rarely happens in practice, though, because more often than not the images of underweight avatars will simply make average- and women in larger bodies feel bad about themselves.[8] The narrow range of avatar customization available in the most popular virtual worlds, along with the pressure from oneself and others to create an “improved” avatar, means that the freedom to customize one’s appearance in virtual worlds mostly results in even more insecurity about appearance and body size.

Social networks and online communities

A meta-analysis of studies from 17 countries has found that using social media is associated with body image concerns and disordered eating:[9] as Virginia Sole-Smith puts it in her book Fat Talk, “social media has become a place where kids learn the customs, vernacular, and rules of diet culture and anti-fat bias.”[10] While social networks allow users to post a wide variety of things, from videos to random thoughts, one of the most commonly shared items among young people is photos. There is a strong pressure to make those photos (particularly profile photos, which are visible to all the other users one interacts with and are fully public on the Web) look as attractive as possible – in this case, through the use of flattering camera angles and image-manipulation software such as filters. This takes image-improvement techniques that had traditionally been the preserve of models and celebrities, such as staging, manipulating and editing photos, and makes them available to anyone who is concerned about their appearance.[11] Perhaps not surprisingly, people who base their self-esteem primarily on how they are seen by others – including how they see their appearance – share photos more than those whose self-esteem is based on factors such as intelligence or achievement.[12]

Kaitlyn Axelrod, outreach coordinator for eating disorder support group Sheena’s Place, explains that “with social media, it’s very sneaky because especially with Instagram and Tik Tok, these apps that are meant to capture what’s going on in the life of someone, they can make people think that other people’s lives look a certain way. And then that can cause comparisons that are even more damaging than if someone just sees a model or someone who they find really attractive on TV.”[13]

While youth primarily use social networks to keep in touch with their offline friends, online communities facilitate connections with people around the world who share the same interests. While this can often be very positive, particularly for those who live in small or isolated communities, these online communities can also reinforce negative attitudes towards body image. Most notorious are the so-called “pro-ana” communities, which consist of websites, blogs and blogrings (blogs linked by a particular topic) and even discussion groups on social media sites such as Snapchat or Instagram that promote “thinspiration” and how to reach an idealized body type in an unhealthy manner.[14] In recent years, social networks have been recommending algorithmically-curated content in addition to the accounts that users follow; on some, such as TikTok, this now makes up most of what young people see. This means that youth can see stigmatizing and unhealthy content even if they don’t seek it out. Research has found, for instance, that pro-eating disorder content appears on TikTok’s “For You” feed,[15] though TikTok blocked access to related search terms after the study was published. Another study, meanwhile, found that the majority of videos related to food or weight on TikTok “presented a weight-normative view of health” and glorified weight loss.[16] Research on Instagram, similarly, found that its recommendation algorithm promoted pro-eating disorder content to users with a median age of 19.[17]

Some social networks, such as Snapchat, have also begun integrating “chatbots” that use machine learning algorithms to mimic conversations with users. Like recommendation algorithms, these chatbots frequently provide content that promotes negative body image and sometimes even pro-eating disorder content, such as the 700-calorie-a-day meal plan recommended by Snapchat’s My AI.[18] Similarly, algorithmic image generators such as Dall-E and Midjourney are able to create images that promote unhealthy weight ideals.[19]

As Shirley Cramer, chief executive of the Royal Society for Public Health in the UK, puts it, “social media is now a part of everyone’s life…[and] we must therefore strive to understand its impact on mental health and especially the mental health of the younger [female] population.” Cramer believes that the highest prevalence of the social media impact is seen on young people aged 16-24. As a participant in Cramer’s study said, “Instagram easily makes girls and women feel as if their bodies aren’t good enough.”[20] This likely stems from the constant digital manipulation of photos posted to the social media platform, which causes young girls to feel as though they could never reach that ideal body type, even though the ideal body type they are comparing themselves to is not real.

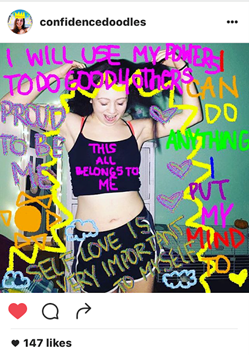

There is strong evidence, though, that it is not simply using social media that causes these effects but how social media are used. While browsing idealized images, or “fitspo” content aimed at encouraging weight loss was associated with lower body satisfaction, viewing body-positive content on Instagram has been found to make women more satisfied with their bodies.[21] Young people have also used hashtags like #AcnePositivity and #BodyHairPositivity to push back against media beauty standards,[22] and there are many popular accounts promoting body positivity and healthful diets. Even there, though, author Virginia Sole-Smith points out that they typically still follow Instagram aesthetics: “When treat foods are featured, it’s only in tiny, perfectly photogenic portions: one adorable mini muffin with rainbow sprinkles, or three M&M’s added as garnish to a lunch featuring three pieces of fruit.”[23]

Online influencers are another form of advertising and source of body image issues for teens. Some social networks popular with teens have taken steps to address this. Instagram, for example, changed its policies in 2019 to stop the promotion of weight loss products and cosmetic procedures. Emma Collins, Instagram’s public policy manager stated, "we want Instagram to be a positive place for everyone that uses it and this policy is part of our ongoing work to reduce the pressure that people can sometimes feel as a result of social media.” Whether or not they’re promoting weight loss products, though, constant exposure to ideal – and frequently photo-manipulated – images of men and women’s bodies has an impact, even when viewers are aware that the images have been altered. [24] Unlike traditional advertising, influencer ads are viewed alongside pictures of a young person’s peers, which have a similar effect on views of one’s own body. [25] As a result, many adolescents feel the only way to achieve this “model status” is to use diet products advertised to them online that show digitally manipulated models they strive to look like.[26] Social media – and influencers in particular – have also been central to the promotion of weight-loss drugs, which can be advertised directly to consumers even in countries where they have not been approved (or approved for weight-loss use).[27]

Photo manipulation

Photo manipulation, once the preserve of a small number of airbrush-equipped artists, has become commonplace in the fashion, publishing and advertising industries thanks to the introduction of photo-editing software such as Photoshop and filters on social media such as Instagram. Photoshop, first introduced in 1990, has become so widely used that “photoshopping” is often used as a synonym for photo manipulation. As a result, heavily retouched photos – of men as well as women[28] – have become almost universal, with industry figures claiming that nearly all photos in magazines are edited.[29] While downloads of the most widely-known photo-manipulation app, Facetune, have declined by more than three-quarters since their peak,[30] this may be because similar functions have been built into the apps themselves: “an image cannot be uploaded without different filter options appearing automatically.”[31]

“When I take a picture with no filter and that picture does not receive the number of likes I am expecting, it makes me feel bad about myself. Like for me to look ‘perfect’ and ‘liked’ I need to take pictures with filters.”[32]

As photo manipulation tools have become more widely available and easier to use, youth have begun turning to them to modify their own photos to meet media-created ideals of thinness and perfection. These tools have been linked to “Snapchat dysmorphia,” a desire to alter one’s own body to look more like your selfies.[33]

Retouching photos in this way raises a number of concerns. One is that the already unrealistic bodies youth are exposed to are made literally impossible. Senior graphic designers have admitted that editing includes retouching everything, “they elongate necks. They tuck in arms. They take out veins.”[34] Even models have stated they, at times, feel inadequate and say they if they don’t like the way they look to photographers they claim they can edit that part out.[35] This guarantees that even those who meet media standards of attractiveness will still be left feeling inferior (this is a Digital Age twist on the old “ring around the collar” tactic of creating anxieties that consumers didn’t know they had).[36]

For boys, as well, the combination of social media, image modification and performance-enhancing drugs can be dangerous. Robert Olivardia, a specialist in treatment of body dysmorphia, has said that “young boys are getting information about the substances and have access to imagery — and it’s not only just celebrities now. It’s their peers, and they’re Photoshopping pictures of themselves.”[37] As well, photo manipulation reduces the diversity represented in media, pushing everyone towards a single standard. Besides limited body shapes, social media has led to the adoption of what’s called “Instagram face”: “ethnically ambiguous and featuring the flawless skin, big eyes, full lips, small nose, and perfectly contoured curves made accessible in large part by filters.”[38]

These issues may lead to negative effects on young people’s self-image and self-esteem. Rahaf Harfoush, a digital anthropologist and executive director of the Red Thread Institute of Digital Culture, points out that compared to traditional media, “instead of seeing somebody who had a face that didn’t look like yours — and seeing that beauty standard as external — we’re essentially taking those beauty standards and superimposing them on our own faces. We’re then just emphasizing this ‘lack,’ which I think is very damaging to people.”[39] At the same time, there is evidence that like avatars, filters and similar tools can have positive effects in certain contexts, such as when used by transgender youth to help affirm their gender identities.[40]

It’s hardly a secret that many bodies seen in media are digitally manipulated. Unfortunately, just knowing that images are manipulated doesn’t defuse their effects. Placing disclaimers on photos stating that they’ve been manipulated doesn’t reduce their effects on body dissatisfaction, as women still find photos realistic even when told they were digitally manipulated.[41] As Dr. Kim Bissell, founder of the Child Media Lab at the University of Alabama, said, “We know they’re Photoshopped, but we still want to look like that.”[42]

In fact, young girls often use photo manipulation software to retouch their own photos. Connie Morrison, in her book Who Do They Think They Are? Teenage Girls & Their Avatars in Spaces of Social Online Communication, says “girls understand that the images on television and in magazines are manipulated, and for some this understanding seems to lead to an expectation that they can (or should) be doing the same.” As one of the girls she interviews puts it, “It makes me more comfortable… when my profile picture is something that looks flawless and ‘pretty’ even though I know it’s fake.”[43]

If you or someone you know needs support in dealing with an eating disorder, visit the National Eating Disorder Information Centre.

[1] Martins, N., Williams, D. C.,Harrison, K., & Ratan, R. A. (2009).A content analysis of female body imagery in video games. Sex Roles, 61(11-12), 824-836.

[2] Martins, N., Williams, D. C., Ratan, R. A., & Harrison, K. (2011). Virtual muscularity: A content analysis of male video game characters. Body Image, 8(1), 43-51.

[3] Dingelfelter, S. Video game magazines may harm boys’ body image. Monitor on Psychology October 2006, 37:9.

[4] Grimes S. “I’m a Barbie Girl, in a BarbieGirls World.” The Escapist, 165, September 2, 2008.

[5] Morrison, C (2010) Who do they think they are? Teenage girls and their avatars in spaces of social online communication. Peter Lang.

[6] Yee, Nick and Bailenson, Jeremy. (2007) The Proteus Effect: The Effect of Transformed Self-Representation on Behavior. Human Communication Research 33(3):271 – 290. DOI: 10.1111/j.1468-2958.2007.00299.x

[7] Riva, G et al. (2016) Virtual worlds versus real body: Virtual reality meets eating and weight disorders. Cyberpsychology, Behaviour and Social Networking Journal. 19(2). 63-66

[8] Dirk Smeesters, Thomas Mussweiler, and Naomi Mandel. “The Effects of Thin and Heavy Media Images on Overweight and Underweight Consumers: Social Comparison Processes and Behavioral Implications.” Journal of Consumer Research: April 2010.

[9] Dane, A., & Bhatia, K. (2023). The social media diet: A scoping review to investigate the association between social media, body image and eating disorders amongst young people. PLOS Global Public Health, 3(3), e0001091.

[10] Sole-Smith, V. (2023). Fat talk: parenting in the age of diet culture. First edition. New York, Henry Holt and Company.

[11] Stefanone, Michael et al. Contingencies of Self-Worth and Social-Networking-Site Behavior. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, And Social Networking.14:1-2, 2011.

[12] Stefanone, Michael et al. Contingencies of Self-Worth and Social-Networking-Site Behavior. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, And Social Networking.14:1-2, 2011.

[13] Quoted in Aziz, S. & Young, L. (2022) “Instagram vs reality The perils of social media on body image.” Global News. https://globalnews.ca/news/8506592/social-media-influenced-body-image/

[14] Cohen, Alex. Countering the Online World of ‘Pro-Anorexia’. Day to Day, February 27, 2009. http://www.npr.org/templates/story/story.php?storyId=101210192

[15] Little, O. (2023) TikTok is hosting pro-anorexia content that targets children. Media Matters for America. https://www.mediamatters.org/tiktok/tiktok-hosting-pro-anorexia-content-targets-children

[16] Minadeo, M., & Pope, L. (2022). Weight-normative messaging predominates on TikTok—A qualitative content analysis. Plos one, 17(11), e0267997.

[17] Wong, Q. (2022) “Designing for Disorder: Instagram’s Pro-eating Disorder Bubble.” CNET. https://www.cnet.com/news/social-media/instagram-promotes-pro-eating-disorder-content-to-kids-report-says/

[18] Fowler, G. (2023) “AI is acting ‘pro-anorexia’ and tech companies aren’t stopping it.” The New York Times. https://www.washingtonpost.com/technology/2023/08/07/ai-eating-disorders-thinspo-anorexia-bulimia/

[19] (2023) AI and Eating Disorder: How generative AI is enabling users to generate harmful eating disorder content. Center for Countering Digital Hate. https://counterhate.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/08/230705-AI-and-Eating-Disorders-REPORT.pdf

[20] Royal Society for Public Health. (2017, May) Status of mind: Social media and young people’s mental health and wellbeing. Retrieved from https://www.rsph.org.uk/our-work/campaigns/status-of-mind.html

[21] Cohen, Rachel et al. (2019) #BoPo on Instagram: An experimental investigation of the effects of viewing body positive content on young women’s mood and body image. New Media and Society, 21:7. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444819826530

[22] Cornall, F. (2023) “From diversity to accessibility, can technology change the way we think about beauty for the better?” CNN. https://www.cnn.com/style/article/beauty-technology-spc-intl/index.html

[23] Sole-Smith, V. (2023). Fat talk: parenting in the age of diet culture. First edition. New York, Henry Holt and Company.

[24] Mariska Kleemans, Serena Daalmans, Ilana Carbaat & Doeschka Anschütz (2018) Picture Perfect: The Direct Effect of Manipulated Instagram Photos on Body Image in Adolescent Girls, Media Psychology, 21:1, 93-110, DOI: 10.1080/15213269.2016.1257392

[25] Jasmine Fardouly, Lenny R. Vartanian, Negative comparisons about one's appearance mediate the relationship between Facebook usage and body image concerns, Body Image, Volume 12, 2015, Pages 82-88, ISSN 1740-1445, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2014.10.004

[26] Thorbecke, K (2019) Instagram announces new policies for promoting diet products, cosmetic procedures. ABC News. Retrieved from https://abcnews.go.com/Business/instagram-announces-policies-promoting-diet-products-cosmetic-procedures/story?id=65716682

[27] Tait, A. (2023) Weight loss injections have taken over the internet. But what does this mean for people IRL? MIT Technology Review. https://www.technologyreview.com/2023/03/20/1070037/weight-loss-injections-societal-impact-ozempic/

[28] “The Complicated Art of Airbrushing Abdominals.” Jezebel, October 7, 2010. <http://jezebel.com/5658169/the-complicated-art-of-creating-abdominals?tag=photoshopofhorrors>

[29] Bruner, R (2018). Blake Lively says 99.9% of celebrity images are photoshopped while interviewing Gigi Hadid. Time. Retrieved from https://time.com/5236384/blake-lively-photoshop-gigi-hadid-interview/

[30] Woodbury, R. (2021) “The Rejection of Internet Perfection.” Digital Native. https://digitalnative.substack.com/p/the-rejection-of-internet-perfection

[31] Naderer, B., Peter, C., & Karsay, K. (2022). This picture does not portray reality: developing and testing a disclaimer for digitally enhanced pictures on social media appropriate for Austrian tweens and teens. Journal of Children and Media, 16(2), 149-167.

[32] Eshiet, J. (2020) “Real Me Versus Social Media Me: Filters, Snapchat Dysmorphia, and Beauty Perceptions Among Young Women.” Electronic Theses, Projects, and Dissertations. 1101. https://scholarworks.lib.csusb.edu/etd/1101

[33] Eshiet, J. (2020) “Real Me Versus Social Media Me: Filters, Snapchat Dysmorphia, and Beauty Perceptions Among Young Women.” Electronic Theses, Projects, and Dissertations. 1101. https://scholarworks.lib.csusb.edu/etd/1101

[34] Shen, S (2014) Photoshop: The tool to being unrealistically gorgeous. AI Standard. Retrieved from https://web.archive.org/web/20151123154944/https://sites.psu.edu/shelleyshen/wp-content/uploads/sites/26834/2015/04/Photoshop.pdf

[35] Bruner, R (2018). Blake Lively says 99.9% of celebrity images are photoshopped while interviewing Gigi Hadid. Time. Retrieved from https://time.com/5236384/blake-lively-photoshop-gigi-hadid-interview

[36] Copeland, Libby. “How advertisers create body anxieties women didn’t know they had and then sell them the solution.” Slate, April 14, 2011.

[37] Quoted in Abad-Santos, A. (2021) “The open secret to looking like a superhero.” Vox. https://www.vox.com/the-goods/22760163/steroids-hgh-hollywood-actors-peds-performance-enhancing-drugs?utm_campaign=vox.social&utm_source=facebook&utm_content=voxdotcom&utm_medium=social

[38] Ryan-Mosley, T. (2022) The fight for “Instagram face.” MIT Technology Review. https://www.technologyreview.com/2022/08/19/1057133/fight-for-instagram-face/

[39] Quoted in Passafiume, A. (2023) “TikTok’s Bold Glamour filter is so good it might be bad for you. Here’s why experts are concerned.” The Toronto Star. https://www.thestar.com/life/tiktok-s-bold-glamour-filter-is-so-good-it-might-be-bad-for-you-here/article_b371af93-a466-58a6-9aca-72f8fc484995.html

[40] Smith, A. (2022) “AI image app Lensa helps some trans people to embrace themselves.” Reuters.

[41] Mcbride, C et al. (2019) Digital Manipulation of Images of Models’ Appearance in Advertising: Strategies for Action Through Law and Corporate Social Responsibility Incentives to Protect Public Health. Boston University School of Law. 45(2019). 7-31.

[42] Stalnaker, Deidre. “On the Cover, In the Mirror.” Research Magazine, January 21, 2010.

[43] Morrison, Connie. Who Do They Think They Are? Teenage Girls & Their Avatars in Spaces of Social Online Communication. Peter Lang Publishing, New York. 2010.