Techniques for literacy

Researchers have identified three general responses when people become aware of surveillance and algorithmic profiling: first, ignoring what they have learned and continuing to use the services as before; second, self-inhibition by limiting things like online searches, content of online posts and which online services are used; and third, the use of privacy-enhancing techniques.[2]

It's easy for both adults and young people to fall into one of the first two responses, but privacy advocates stress that there are things we can do that help manage our privacy without completely locking down our online experience. As William Budington of the Electronic Frontier Foundation says, “There are things you can do to protect your privacy by 85, 90, 95 percent that will not add much friction to your life.”[3]

The role of parents: to spy or not to spy?

Parents are one of the most important resources for young people in learning how to manage both their social and data privacy. At the same time, as noted above, parents often feel pressure to use surveillance tools on our children. This pressure can be increased by the fact that parents are one of the audiences kids are most likely to hide online content from.[4]

As parenting expert Devorah Heitner points out, however, this kind of surveillance can backfire by giving us “a false sense of security… That dot on the geo-tracking app doesn’t always tell us much. Kids can be at the library studying with friends, or in the study room goofing off with friends, or behind the library vaping. The app will show them... at the library in all these instances.”[5] Heitner also points out that surveillance models attitudes towards privacy that are the direct opposite of the ones we want our children to adopt.

In general, therefore, it’s best to only directly surveil kids online if there is a clear and present reason to do so – if they have done something that shows they need close supervision, for instance. Even in this case, however, parents should be open about the surveillance and clear about both the reasons why we are doing so and under what conditions we’ll stop. Doing so “openly and in communication with our kids can be part of mentoring, especially if we have a plan and criteria for backing off as they get older and we see they are just fine.”[6]

Not surveilling kids, however, doesn’t mean not supervising them. With younger kids, that may be as simple as making sure that all connected devices are used in public parts of the house and walking by every now and then to check in. During the tween years, making shared social network accounts can be a form of “training wheels” that also allow them to use their real age when they do create their own account at 13 or older (many social networks now have special protections and more secure default settings for users aged 13-18). At all ages, it is essential to have an ongoing conversation about their media lives, clearly communicate your values and expectations through household rules and model the kind of behaviour you want to see.[7],[8]

Teaching privacy skills and habits

What we need to teach kids about privacy – and what they’re ready to learn – changes as they get older:

- Five to seven years old: At this age, children are already using services that collect and share their data. Their perception of risks with technology are mostly physical threats to their devices. Parents of kids in this age range have to take most of the responsibility for protecting children’s privacy by choosing apps with good privacy practices and limiting data collection (see more details on how to do that below), but we can still teach kids to come to us for help if they experience any issues, including privacy-related ones.[9]

- 8-11 years old: Children at this age “struggle to fully understand online privacy risks, especially those associated with implicit personal data collection and use, through mechanisms such as data tracking or in-app recommendations.“[10] While they do find privacy intrusions, such as internet-connected toys, to be “creepy” or worrying, they’re likely to overlook this if it has a cute or unthreatening appearance.[11] Clear and simple rules about what they can or shouldn’t share – as well as when to ask you for help – are generally effective.[12] Towards the end of this period, they can begin to understand privacy as being contextual: things that might be appropriate for some audiences to see are not appropriate for others.[13]

At this age kids are more likely to see privacy in terms of not letting “strangers” see their content, rather than controlling audiences or limiting data collection. However, they can learn positive privacy habits and practices through interactive and scaffolded learning experiences.[14]

- 12-17 years old: Young people this age are aware of privacy risks, but still focus on interpersonal ones as they see the online world as a space to socialize and express themselves.[15] They rarely consider commercial use of their data – for example, only half of UK teens aged 12-15 know that both YouTube and Google are funded by the companies that advertise with them[16] – and when they do, they are generally unaware of the ways in which their data may move between platforms online.[17]

It's important, however, not to impose our ways of thinking about privacy on them. Research into young people’s privacy practices has found, for instance, that they’re more likely to focus on managing a privacy issue after it has occurred rather than working to prevent it beforehand, “leading to privacy-preserving behaviors (e.g., advice-seeking) and remedy/corrective risk-coping behaviors (e.g., deleting content, blocking another user, deactivating their account).”[18]

When something does go wrong, therefore, our response should not be to assume they don’t care about privacy or criticize them for the choices that may have led to it, but rather to ask “How can we fix this, and what can we do to prevent it from happening next time?”[19]

At the same time, we have to recognize that young people’s retroactive approach to privacy issues doesn’t work well in dealing with data privacy issues. Though they’re generally less conscious of data privacy compared to social privacy, young people do “look to trusted adults as proxies for detecting creepy or otherwise untrustworthy technologies.”[20] We also shouldn’t assume that data privacy is only an issue once they reach the tween or teen years. In fact, numerous studies have found that young people experience intense data collection as soon as they begin using digital devices.[21],[22],[23]

Media education and privacy

Media education “plays an important part in how children understand, manage and safeguard their privacy.”[24] Parents, teachers and other trusted adults can help kids manage their social and data privacy by helping them develop MediaSmarts’ core competencies of digital media literacy – specifically, being able to use, understand and engage with media. Look for opportunities like getting a new device, starting to use a new app or social network account, or a privacy-related anecdote or news story they may have heard.[25]

Use: There are many practical steps that parents and youth can take to manage both their social and data privacy:

- As early as possible, model good privacy behaviours by asking your kids before you post anything about them.[26] Tell them what audiences you think might see what you post and explain what you’ll do to limit who else can see it.

- Install privacy-protecting plugins such as Privacy Badger on laptops and desktops and apps such as DuckDuckGo or Do Not Track Kids on mobile devices.

- Review what information different apps are collecting on mobile devices and teach kids how to do this themselves, as well.

- Teach young people to review and customize privacy settings. MediaSmarts’ research has found that half of Canadian kids have learned how to do this from their parents.[27] These settings are primarily used to control social privacy, but they increasingly offer options to limit data collection (or the use of users’ data for things like targeted advertising) as well – though these tools are often accessed in different places than the standard privacy settings.

- Make sure youth know that most social networks allow you set custom privacy levels for individual posts, as well as general settings.

- Make sure to regularly review the default privacy settings, which may change with little notice, and watch for communications from the platform about changes to them.[28]

- Teach kids not to sign in to any apps or websites using their social network logins. You can also show them how to create secure and disposable email addresses using Protonmail or Sharklasers if they want to register for something without giving away their regular email address.

- Learn together how to limit apps’ permission to a device’s camera, microphone and location.

- Learn how to skim privacy policies for the most important information, and teach older kids to do this as well. To find the most important information, look or search for section titles like:

- “Personal information we collect” or “How we collect your personal data.”

- “Geolocation” or “geotargeting”: If an app wants to access your location for reasons that don’t make sense to you, you may need to turn off GPS on your device.

- “How we use your personal information”: Look for vague phrases like “business activities” or “business purposes.”

- “Personalize,” “enhance,” “improve your services” or “interest-based advertising”: If the policy contains any language like this, find out if you can turn off algorithmic sorting (such as by switching from the “For you” to the “Following” feed) and targeted advertising.

- “Your rights” or “your choices”: This will usually lay out what options they have to give you under the laws where you live.[29]

- You can also visit the website Terms of Service – Didn’t Read, which rates and reviews different apps and websites’ privacy policies. Common Sense Media also evaluates apps’ privacy practices and Mozilla has privacy reviews of mental health apps, toys and games, entertainment devices like e-readers and smart devices.

- If your kids use iOS devices such as iPhones or iPads, teach them to refuse data collection when installing new apps. If they use Android devices, install the DuckDuckGo app and turn on App Tracking Protection.

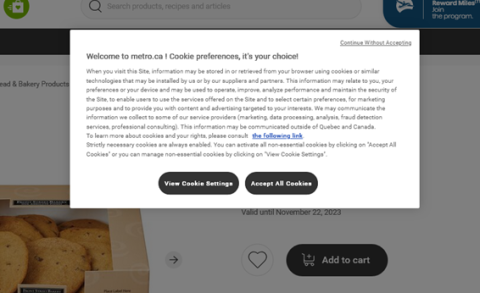

- Teach kids to accept only the minimum required level of data collection on websites – first, by never clicking “Accept All”:

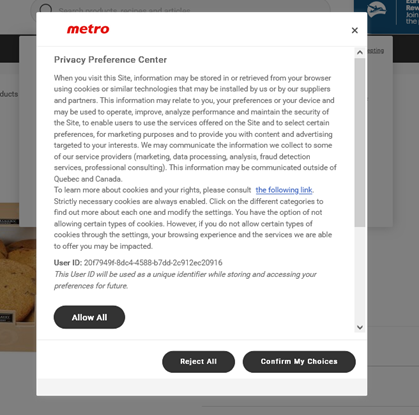

And then by looking for phrases like “Reject All” or “Only Necessary”:

Understand: The digital and media literacy key concepts listed below are helpful for framing discussions about media representation and privacy. For each one, a series of questions has been provided that encourage youth to protect their personal information in the online world while strengthening their privacy:

Media are constructions that re-present reality. Ask:

- Who created the apps, platforms and tools I use?

- How do targeted advertising and recommendation algorithms affect what content I see online?

- What might your data profile (all of your data that’s been collected) say about you? Do you think it would be an accurate image? Is there data that might give an inaccurate idea about you?

Media have social and ideological implications. Ask:

- Are there important misconceptions that people have about social or data privacy? What are they?

- How do you think the people who make apps and websites think about privacy? Is it different from how you do?

- Have you seen privacy issues represented in news or entertainment media? What impressions did you get from them about personal or data privacy? What lessons did you take away from them?

Media have commercial implications. Ask:

- How do the apps and websites you use make money? How are data collection and targeted advertising part of that?

- Are some of the apps or websites you use owned by larger corporations? (For instance, Meta owns both Instagram and Facebook, and Alphabet owns Google and YouTube.) How might information about you that is shared between these (which may not be considered “sharing data” in the privacy policy) affect your experience of them?

- Do corporations allow their terms and conditions to be easily understood? Why or why not?

- Could it be harmful if online users aren’t able to give informed consent to their personal data being collected? Why or why not?

- Does what you see online, through advertisements, influence your financial decisions and what you buy?

- What apps and platforms follow best practices for respecting young people’s privacy? Look for ones that collect minimal data, like Kolibri, or use verifiable parental consent before collecting data, like Lego’s digital products.[30]

Audiences negotiate meaning in media. Ask:

- How might something you share online be interpreted differently by different people? Are there ways that this could have negative effects? For example, are there signs that might show your friends that a post was a joke or sarcastic that might be missed by other people?)

- Devorah Heitner recommends asking kids to consider whether they would be willing to wear something they post on a T-shirt that they wore in public: “If they are comfortable wearing it on a T-shirt, then disclosing it on social media could feel fine.”[31]

- How do you think the adults in your life think about privacy? Is it different from how you do?

Each medium has a unique form. Ask:

- What messages do different apps and websites communicate about privacy through their “look and feel”? Which ones feel more casual and which feel more serious?

- How are privacy policies written? What are the most important things to look for? (See tips in the “Use” section above.)

Digital media are networked. Ask:

- How are the different apps, websites and tools you use connected?

- How could things you share, intentionally or unintentionally, be spread through those network connections?

- Think about an online experience where it doesn’t feel like you’re sharing any data (for example, watching a streaming service like Crave or Netflix). What information are you sharing?

Digital media are shareable and persistent. Ask:

- How might content you share stay online longer than you mean it to?

- How can you limit who else might be able to share your content?

- How can you delete your content online (for example, asking someone who has shared a photo of you to take it down)?

Digital media have unexpected audiences. Ask:

- Who was the intended audience for what you posted? How did the intended audience influence how it was made? For example, how would a photo you post for your friends to see be different from one for your parents or a romantic partner?

- How might using social steganography – sending a message through things like in-jokes, memes, song lyrics, and so on, that only certain people will understand – backfire if it’s seen by the wrong audience?

- What information might you be sharing without knowing it when using different apps, websites or tools? What “third parties” might they be sharing it with?

- What might data brokers – who collect information from many sources to build a profile of you – know, or think they know, about you?

Digital media experiences are shaped by the tools we use. Ask:

- What are different apps or tools’ affordances – in other words, what does the tool let you do? For example, are there limits on how many photos you can post to your account at one time?

- What are the apps or tools’ defaults – the things that the tool lets you do without having to specifically choose them? For instance, photos self-destruct by default on Snapchat, but on Instagram you have to choose to do that.

- How do the affordances and defaults influence how much you share with other users and how much data you share with the platform? What things are easy to do and what are more difficult or take more steps to do?

- Is deceptive design (or “dark patterns”) used to make you share more than you otherwise would with other users or share more data with the platform?

Interactions through digital media can have a real impact. Ask:

- How might things you share online affect other people?

- How can you limit or control the effect online sharing has on others (for instance, by asking before you share photos or videos of them)?

- How can data collected by corporations affect you, now or in the future?

- What can you do to advocate for better privacy practices?

Engage:

As valuable as learning to use and understand media is in addressing privacy issues, it has its limits. As scholar Sonia Livingstone put it, “we cannot teach what is unlearnable, and people cannot learn to be literate in what is illegible.”[32] For this reason, parents and young people also need to use media tools to advocate for corporations and governments to adopt best practices for handling personal information and empowering youth privacy:

- Design apps and platforms, including features related to social and data privacy, with young people in mind and with a goal of respecting and protecting their privacy,[33] and have privacy and safety teams work together with engineers from the beginning of the design process;[34]

- Design apps and platforms for teens that “encourage [them] to reflect on and self-regulate their own behaviors” instead of encouraging parental surveillance and control;[35]

- Design apps and platforms to proactively teach users about their data collection practices and encourage them to choose preferences they are comfortable with;[36]

- Make privacy policies that are shorter,[37] simpler, more accessible and transparent, provide users with options to opt in and out of specific data collection features and confirm that they understand the privacy policy before collecting and information;[38]

- Do not track young users across apps and platforms and develop identifiers needed to track functioning and use that cannot be linked to their identities;[39]

- Make the opting-out process simpler and clearer, and do not use “dark patterns” or other design elements that nudge users to give up more data than they intend to;[40]

- Inform youth about their rights to privacy and give them guidance on how to protect and manage their personal information;[41]

- Give young people easy access to information collected about them as well as easy tools to delete or correct it;[42]

- Consider the possible impacts of technologies on marginalized and disadvantaged groups, including youth, starting at the design stage and drawing on their input. As Virginia Eubanks, author of Automating Inequality, puts it, “We don’t need to project potential harms into an abstract future; we can ask people what they experienced last week. We have to build explicitly political tools to deal with the explicitly political systems they are operating in… We have to build our values into our design practices and be clear about them.”[43]

While these strategies and techniques work at an individual level, there are also a number of strategies designed to protect privacy in place at the provincial, territorial, federal and international levels. The next section outlines some of the major pieces of Canadian, American and international privacy legislation.

[1] Dowthwaite, L., Creswick, H., Portillo, V., Zhao, J., Patel, M., Vallejos, E. P., ... & Jirotka, M. (2020, June). " It's your private information. it's your life." young people's views of personal data use by online technologies. In Proceedings of the interaction design and children conference (pp. 121-134).

[2] Kappeler, K., Festic, N., & Latzer, M. (2023). Dataveillance imaginaries and their role in chilling effects online. International Journal of Human-Computer Studies, 179, 103120.

[3] Quoted in Cushing, E. (2023) The Atlantic’s guide to privacy. Retrieved from https://www.theatlantic.com/technology/archive/2023/09/managing-digital-privacy-personal-information-online/675184/

[4] MediaSmarts. (2022). “Young Canadians in a Wireless World, Phase IV: Online Privacy and

Consent.” MediaSmarts. Ottawa.

[5] Heitner, D. (2023) Growing Up in Public. Penguin Publishing Group

[6] Heitner, D. (2023) Growing Up in Public. Penguin Publishing Group

[7] MediaSmarts. (2022). “Young Canadians in a Wireless World, Phase IV: Online Privacy and

Consent.” MediaSmarts. Ottawa.

[8] Brisson-Boivin, K. (2018) The Digital Well-Being of Canadian Families. Ottawa, ON.

[9] Livingstone, S., Stoilova, M., & Nandagiri, R. (2019). Children's data and privacy online: growing up in a digital age: an evidence review.

[10] Dally, C et al. (2019) ‘I make up a silly name’: Understanding Children’s Perception of Privacy Risks Online. In CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems Proceedings (CHI 2019), May 4-9, 2019, Glasgow, Scotland UK. ACM, New York, NY, USA, 13 pages.

[11] Yip, J. C., Sobel, K., Gao, X., Hishikawa, A. M., Lim, A., Meng, L., ... & Hiniker, A. (2019, May). Laughing is scary, but farting is cute: A conceptual model of children's perspectives of creepy technologies. In Proceedings of the 2019 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (pp. 1-15).

[12] Livingstone, S., Stoilova, M., & Nandagiri, R. (2019). Children's data and privacy online: growing up in a digital age: an evidence review.

[13] Nissenbaum, H. (2020). Privacy in context: Technology, policy, and the integrity of social life. Stanford University Press.

[14] Livingstone, S., Stoilova, M., & Nandagiri, R. (2019). Children's data and privacy online: growing up in a digital age: an evidence review.

[15] Livingstone, S., Stoilova, M., & Nandagiri, R. (2019). Children's data and privacy online: growing up in a digital age: an evidence review.

[16] Polizzi, G (2021). Comparing Children’s Understanding of Data and Online Privacy with Experts and Advocates’ Digital Literacy Practices. Information Literacy Group. Retrieved from https://infolit.org.uk/guest-blog-post-digital-and-data-literacy-comparing-childrens-understanding-of-data-and-online-privacy-with-experts-and-advocates-data-literacy-practices/

[17] Livingstone, S, Nandagiri, R & Stoilova, M (2018). Children’s data and privacy online: Growing up in the digital age. LSE Media and Communications. Online.

[18] Wisniewski, P. J., Vitak, J., & Hartikainen, H. (2022). Privacy in adolescence. In Modern socio-technical perspectives on privacy (pp. 315-336). Cham: Springer International Publishing

[19] Wisniewski, P. J., Vitak, J., & Hartikainen, H. (2022). Privacy in adolescence. In Modern socio-technical perspectives on privacy (pp. 315-336). Cham: Springer International Publishing.

[20] Yip, J. C., Sobel, K., Gao, X., Hishikawa, A. M., Lim, A., Meng, L., ... & Hiniker, A. (2019, May). Laughing is scary, but farting is cute: A conceptual model of children's perspectives of creepy technologies. In Proceedings of the 2019 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (pp. 1-15).

[21] Zhao, F., Egelman, S., Weeks, H. M., Kaciroti, N., Miller, A. L., & Radesky, J. S. (2020). Data collection practices of mobile applications played by preschool-aged children. JAMA pediatrics, 174(12), e203345-e203345.

[22] Moody, R. (2023) Nearly 1 in 4 children’s Google Play apps breath the ICO’s age-appropriate design code. Comparitech. Retrieved from https://www.comparitech.com/blog/vpn-privacy/app-ico-study/

[23] Foweler, G. (2023) Your kids’ apps are spying on them. The Washington Post.

[24] Livingstone, S., Stoilova, M., & Nandagiri, R. (2019). Children's data and privacy online: growing up in a digital age: an evidence review.

[25] Stoilova, M., Livingstone, S., & Nandagiri, R. (2020). Digital by default: Children’s capacity to understand and manage online data and privacy. Media and Communication, 8(4), 197-207.

[26] Reich, S. M., Starks, A., Santer, N., & Manago, A. (2021). Brief report–modeling media use: how parents’ and other adults’ posting behaviors relate to young adolescents’ posting behaviors. Frontiers in Human Dynamics, 3, 595924.

[27] MediaSmarts. (2022). “Young Canadians in a Wireless World, Phase IV: Online Privacy and

Consent.” MediaSmarts. Ottawa.

[28] Doffman, Z (2021). Has WhatsApp Secretly Changed Yours Privacy Settings? Forbes. Retrieved from https://www.forbes.com/sites/zakdoffman/2021/05/19/apple-iphone-and-google-android-users-do-you-need-to-change-your-whatsapp-settings/?sh=4ebbef0d39a0

[29] Keegan, J., & Woo, J. (2023) How to quickly get to the important truth inside any privacy policy. The Markup. Accessed from https://themarkup.org/the-breakdown/2023/08/03/how-to-quickly-get-to-the-important-truth-inside-any-privacy-policy

[30] Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers. (2022) Applied case studies for designing trustworthy digital experiences for children. Retrieved from https://standards.ieee.org/initiatives/autonomous-intelligence-systems/report-2/

[31] Heitner, D. (2023) Growing Up in Public. Penguin Publishing Group

[32] Livingstone, S. (2018) Media literacy: what are the challenges and how can we move towards a solution? LSE Blog. Retrieved from https://blogs.lse.ac.uk/medialse/2018/10/25/media-literacy-what-are-the-challenges-and-how-can-we-move-towards-a-solution/

[33] Kidron, B., Evans, A., Afia, J., Adler, J. R., Bowden-Jones, H., Hackett, L., ... & Scot, Y. (2018). Disrupted childhood: The cost of persuasive design.

[34] Citron, D. (2022) The Fight for privacy. W.W. Norton.

[35] Wisniewski, P. J., Vitak, J., & Hartikainen, H. (2022). Privacy in adolescence. In Modern socio-technical perspectives on privacy (pp. 315-336). Cham: Springer International Publishing.

[36] Seymour, W., Van Kleek, M., Binns, R., & Shadbolt, N. (2019). Aretha: A respectful voice assistant for the smart home.

[37] Meier, Y., Schäwel, J., & Krämer, N. C. (2020). The shorter the better? Effects of privacy policy length on online privacy decision-making. Media and Communication, 8(2), 291-301.

[38] McAleese, S. (2020). Young Canadians speak out: A qualitative research project on privacy and consent. MediaSmarts.

[39] Zhao, F., Egelman, S., Weeks, H. M., Kaciroti, N., Miller, A. L., & Radesky, J. S. (2020). Data collection practices of mobile applications played by preschool-aged children. JAMA pediatrics, 174(12), e203345-e203345.

[40] Council, N. C. (2018). Deceived by design, How tech companies use dark patterns to discourage us from exercising our rights to privacy. Norwegian Consumer Council Report.

[41] Information and Privacy Commissioner of Ontario. (2023) Digital Privacy Charter for Ontario Schools. Retrieved from https://www.ipc.on.ca/privacy-organizations/digital-privacy-charter-for-ontario-schools/

[42] Office of the Privacy Commissioner of Canada. (n.d.) How organizations can help protect young people online. Retrieved from https://www.priv.gc.ca/en/about-the-opc/what-we-do/provincial-and-territorial-collaboration/joint-resolutions-with-provinces-and-territories/res_231005_01_yth/

[43] Eubanks, V. (2020) Quoted in Public Thinker: Virginia Eubanks on Digital Surveillance and People Power. Public Books. Retrieved from https://www.publicbooks.org/public-thinker-virginia-eubanks-on-digital-surveillance-and-people-power/.