Surveillance techniques

Here are some of the more common kinds of data and ways that it is collected:

Biometric information: Some devices, like smartwatches or fitness trackers, can collect information about things like your temperature and heart rate.

Browsing history: All browsers track what websites you’ve visited. You can keep your computer from remembering that by using that browser’s version of Private or Incognito mode, but the browser may still share it with the company that made it – such as Alphabet (which makes Chrome) and Microsoft (which makes Edge). Some other browsers, such as Firefox and Brave, don’t share or sell any information about you.

Connected toys and smart devices: These may record conversations you have with them (or near them, if you leave them on or accidentally say their wake word) and also data about interactions you have with them. A smart speaker, for instance, may record every question you ask it, every song you play on it and everything you buy with it.

Cookies: Cookies are small files that are placed on a user’s hard drive whenever a website is visited. These let a website remember you and can also connect your profile between sites. On shopping sites, for instance, cookies allow users to select items to purchase, navigate away from the site, and return later to find those items saved in their shopping cart.[1]

Data brokers: Rather than collecting information themselves, data brokers buy it from many different places and put it together. That way, they’re able to assemble a detailed profile or “identity graph” of you and a “social graph” of all your online contacts.

Data scraping: Also known as web scraping, this is the process of collecting publicly available data from across the internet so it can be added to a data profile.

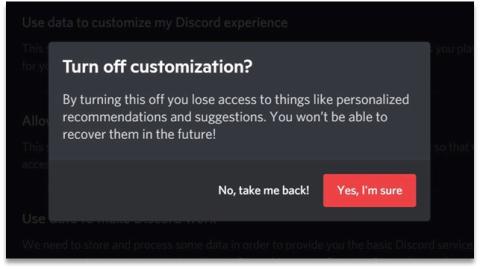

Dark patterns or persuasive design: These are design choices that “nudge” users to do particular things or make certain decisions. In a privacy context, dark patterns make users more likely to do thinks like share personal information, accept data collection or select less protective privacy settings. A recent research project that studied five social networks popular with teens – Discord, Twitter (since renamed X), Instagram, TikTok, and Snapchat – found that all of them used at least one privacy-related dark pattern.

Dark patterns may appear in a site or app’s user interface, in ways like:

- making desired choices easier to do or to find (for instance, by making “Accept All” a single button but forcing users to reject different features one-by-one;

- making the desired choices enabled by default and opt-out (so that users must choose to turn them off) and others opt-in; or

- using language or design features like colour to make the desired choice more attractive.[2]

They can also be a part of an app’s design. One study, for instance, identified three major types of dark patterns in app design:[3]

- obstruction, or making the privacy-protecting choice harder to do (for instance, requiring multiple clicks or taps to turn off data collection);

- obfuscation, by making privacy protections harder to find or making it harder to tell what impact your choice will have on your privacy (for instance, by not being clear about what information is collected when users are in Incognito or Private Browsing mode)[4]; and

- pressure, or making you feel bad about protecting your privacy (this can take the form of persuasion – for instance, by emphasizing what features will not be available if you don’t allow them to collect data – but in some cases it may be more aggressive: YouTube, for instance, displays a blank homepage for users who have turned off their watch history.[5]

Device information: Many websites and apps collect information about how you’re accessing them – everything to the kind of device and which version of the operating system it is using, to the browser you’re using to access a website and even how charged your battery is.[6]

Interactions: Websites and apps track what you do when using them. TikTok, for instance, collects data about which videos you watch to the end, which ones you swipe to finish early, which ones you like or share, and so on.[7]

Location data: Apps will often collect your phone’s location data unless you opt out or turn off your GPS. Your general location data is valuable because it keeps advertisers from showing you ads for things in the wrong place. More fine-grained information about your location may be used to send you personalized offers or make guesses about things like your health, your gender and your interests.

Lookalike audiences: These let platforms target you with ads without sharing your personal information. Once advertisers define the ideal audience for their ads, the app or website can then use its own data to find users who are similar to that ideal audience.

Persistent identifiers: These let platforms or data brokers connect information collected in different places to a single person or device. Examples include advertising ID, Android ID, hardware ID, internet Protocol (IP) address, IMEI (a unique number assigned to every mobile device), MAC address (assigned to internet routers), phone numbers and e-mail addresses,[8] and device fingerprinting (which combines all available data about a device and browser to form a distinct “fingerprint”).

Proxy data: Information about a user that an algorithm can infer (guess) from other data. For example, your search history can be a proxy for your age, based on patterns of what users search for at different ages. Proxy data can let recommendation algorithms deliver content in ways that can be particularly intrusive or, in some cases and countries, even prohibited by law (for example, selecting job ads based on a user’s race). Machine learning algorithms work by finding proxy data that human developers would not be able to see: one resume-scanning algorithm found that the best proxies for whether an applicant would be successful were if their name was Jared and if they played lacrosse in high school. A human, but not an algorithm, would recognize that both of these are very likely proxies for being White, male and upper-class.

Search history: What we search for says a lot about us. Some search engines collect information about your searches to know what ads to show you. Some others, like DuckDuckGo, do not.

Shopping history and loyalty plans: Online retailers like Amazon keep a record of what you buy from them (as well as what you look at but don’t buy: re-targeted ads based on that data are considered especially effective[9]). Loyalty plans, like PC Optimum, also let retailers track what you’ve bought.

Third-party sharing: One of the easiest ways to get data is to get (or buy) it from someone else. Many privacy policies say that they share information with “third party partners” without necessarily naming who they are; even if they are named, they may use your data in ways the original app or website doesn’t. As a result, “it is practically impossible for the consumer to have even a basic overview of what and where their personal data might be transmitted, or how it is used, even from only a single app. The system behind even the most seemingly basic transaction could include hundreds of third parties that all have their own purposes and policies concerning data processing.”[10] Companies that own more than one platform, such as Meta (which owns Facebook and Instagram) or Alphabet (which owns YouTube and Google) can also share data between those platforms. Instagram, for example, uses information from itself and Meta, its parent company, as well as “activity on third-party sites and apps you use”[11]; this can include “the websites and apps you visit, or information advertisers, their partners and … [information that] marketing partners share with [them] that they already have, like your email address.”[12]

Tracking pixels: Also called beacons and web bugs, these are small, transparent images that are placed on websites and are invisible to users.[13] They let the site track where you go and what you do after you have left the site.[14]

This list is by no means complete. Companies are always finding new ways to collect your data, from hyperlinks that include targeting information to ultrasonic beacons that can trigger ads on your phone.[15] Even today’s cars, for example, “are surveillance-machines on wheels souped-up with sensors, radars, cameras, telematics, and apps that can detect everything we do inside – even where and when we do it.”[16]

[1] Cavoukian, A. & Hamilton, T.J. (2002). The Privacy Payoff. Toronto: McGraw-Hill Ryerson Limited.

[2] Kelly, D., & Burkell, J. (2023) Documenting Privacy Dark Patterns: How Social Networking Sites Influence Users’ Privacy Choices.

[3] Kelly, D., & Burkell, J. (2024). Identifying and Responding to Privacy Dark Patterns. FIMS Publications. 385.

[4] Reuters. (2024) Google to destroy billions of private browsing records to settle lawsuit. The Guardian. Retrieved from https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2024/apr/01/google-destroying-browsing-data-privacy-lawsuit

[5] Roth, E. (2023) YouTube will now show a blank homepage if you don’t have watch history on. The Verge. Retrieved from https://www.theverge.com/2023/8/8/23824672/youtube-blank-homepage-watch-history

[6] Williams, D., et al. (2021) Surveilling young people online: An investigation into TikTok’s data processing practices. Reset Australia. Retrieved from https://au.reset.tech/uploads/resettechaustralia_policymemo_tiktok_final_online.pdf

[7] Williams, D., et al. (2021) Surveilling young people online: An investigation into TikTok’s data processing practices. Reset Australia. Retrieved from https://au.reset.tech/uploads/resettechaustralia_policymemo_tiktok_final_online.pdf

[8] Zhao, F., Egelman, S., Weeks, H. M., Kaciroti, N., Miller, A. L., & Radesky, J. S. (2020). Data collection practices of mobile applications played by preschool-aged children. JAMA pediatrics, 174(12), e203345-e203345.

[9] Wagner, K. (2021) Facebook Users Said No to Tracking Now Advertisers are Panicking. Bloomberg.

[10] Myrstad, F., & Tjøstheim, I. (2021). Out of Control. How consumers are exploited by the online advertising industry.

[11] (n.d.) How does Instagram decide which ads to show me? Instagram Help Center. Retrieved from https://www.facebook.com/help/instagram/173081309564229

[12] (n.d.) How does Instagram decide which ads to show me? Instagram Help Center. Retrieved from https://www.facebook.com/help/instagram/173081309564229

[13] (n.d.) Web Bug. PC Mag: Encyclopedia. Retrieved from https://www.pcmag.com/encyclopedia/term/web-bug

[14] Cavoukian & Hamilton, 2002.

[15] Newman, L.H. (2017) Hundreds of Apps Can Listen for Marketing ‘Beacons’ You Can’t Hear. Wired. Retrieved from https://www.wired.com/2017/05/hundreds-apps-can-listen-beacons-cant-hear/

[16] Caltrider, J., et al. (2023) After Researching Cars and Privacy Heres’ What Keeps Us up at Night. Mozilla. Retrieved from https://foundation.mozilla.org/en/privacynotincluded/articles/after-researching-cars-and-privacy-heres-what-keeps-us-up-at-night/