Impact of Online Hate

Radicalization

For many, the biggest concern when it comes to young people and online hate is radicalization. This term refers to the process by which people come to believe that violence against others and even oneself is justified in defense of their own group. Not everyone who is involved in a group is necessarily radicalized to the same degree; in fact, even within a hate group, only a small number of people may be radicalized to the point where they’re ready to advocate and commit violent acts.

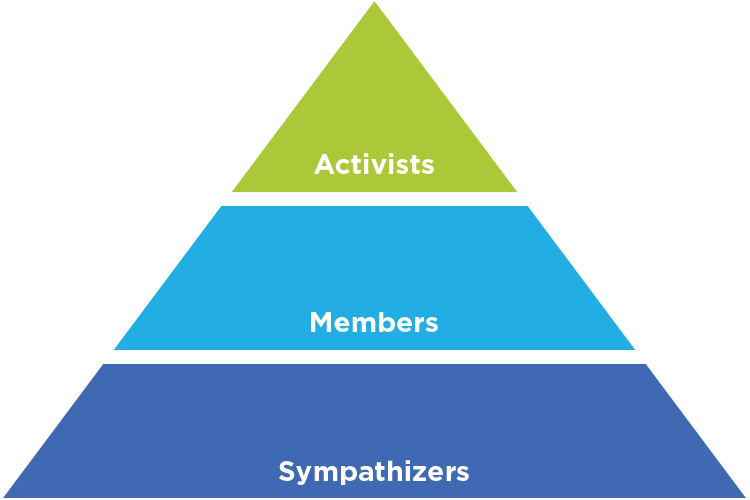

One way of looking at the process is to think of any group or movement as a pyramid.[1] While there has been some recent criticism of this model of radicalization, leading the authors of the original paper to propose a two-pyramid model that separates radicalization of opinion from radicalization of action,[2] it remains a valuable way to model radicalized groups.

The base of the pyramid is made up of sympathizers who support the group and share its ideals but aren’t actively involved in what it’s doing. They’re typically the largest part of the group but also the least committed.

The next level we might call the members. These are people who identify themselves strongly with the group and participate in its everyday activities.

At the final level are activists. These are the members who identify most strongly with the group and are likely to push it towards more radical positions and more extreme actions. The most extreme of these are those who commit violent and other criminal acts. While it’s not always clear how each person becomes radicalized to violence, in Canada alone there have been at least three hate-motivated mass murders whose perpetrators were at least partially radicalized online.[3]

Not all radicalization occurs online, or in hate groups. Offline relationships with family, friends and peers can be an important factor. Some may be radicalized by consuming hate content without ever becoming part of an organized group or community. It’s also important to note that not everyone who is radicalized will move through these steps. In some cases, radicalization will happen suddenly, skipping the sympathizer or member stages or even both.

The process of radicalization has traditionally been seen as the way in which people move up the pyramid to identify more deeply with their group and become more willing to support or engage in extreme acts. The networked nature of digital media, however, allows hate groups and movements to simultaneously target all of the different levels of the pyramid, making it “remarkably easy for viewers to be exposed to incrementally more extremist content”;[4] one scholar has described the internet as a “conveyor belt” to radicalization.[5] On extremist forums, “how to red-pill [i.e. radicalize] others is a constant topic of conversation,” with a great deal of thought put into matching the message with the target’s readiness.[6]

“Hate groups want to recruit the people who start a sentence by saying ‘I’m not racist, but’ … If they’ve said that, they’re almost there. All we have to do is get them to come a little bit further.” Derek Black, former White supremacist[7]

Digital media also enables what’s called reciprocal radicalization, in which audiences push online personalities such as influencers and YouTubers to broadcast more extreme messages.[8] As scholar Becca Lewis puts it,

“Not only are content creators pushing their audiences further to the right, but the reverse happens as well … a lot of times their audiences who are already kind of far-right audiences start demanding more and more far-right content from the people they watch. … So you end up having this kind of vicious cycle where audiences are pushing creators to the right, while creators are also pushing audience members to their right.”[9]

However, it typically takes more than one exposure – or more than one “push” or “pull” factor – to begin the radicalization journey. One typical pattern reported by former extremists is being introduced to online hate content by a friend or acquaintance they know offline – a powerful combination of the ideological and emotional parts of radicalization.

Radicalization and youth

Young people are especially vulnerable to the mechanisms described above because many are looking for groups or causes that will give them a sense of identity. Identity seeking is a natural part of adolescence but, taken to its extreme, this can provide a toe-hold for hate mongers. The term “anomie” describes the state of mind in which family, social or cultural values appear worthless. Youth suffering from anomie will seek a group or cause that gives them values, an identity and a surrogate family.[13] Hate groups and movements take advantage of this to radicalize young people – a process sometimes called "red-pilling," referring to the scene in the movie The Matrix in which the main character takes a pill that will show him the truth about his reality.[14] For many young people, finding an identity – and a group to be part of – may be more important than any actual hatred or ideological commitment.[15] One extremist has said that “ideology is not the primary drive as to why people join these movements. Identity, belonging and a sense of meaning and purpose are far greater draws.”[16]

A common cause of anomie is when changing social conditions make it seem as though one’s identity is under attack. This is often the case when members of historically advantaged groups – White, male, cisgender and abled students – who have been taught an ideal of “colour-blindness” first have to face the real impact these identities have on history and society. As Jennifer Harvey points out in her book Raising White Kids,

“[White students] are less likely to have been actively nurtured in their understanding of race and its meaning in their lives … The racial understanding is underdeveloped, at best, deeply confused at worst. Their experience is something like having only ever been taught basic addition and suddenly being thrown into a calculus class.”[17]

This also explains why economic problems by themselves don’t necessarily make a young person more prone to radicalization: one study found that “it was not poor socioeconomic status itself that pointed toward susceptibility, but rather a sense of relative deprivation, coupled with feelings of political and/or social exclusion.”[18]

Mainstreaming and hostile environments

Beyond radicalizing individuals, the connected, networked nature of online communities also enables hate movements to broaden the base of the pyramid and make hate speech – both in jest and in earnest – seem more acceptable. The purpose is not only to create a greater pool of potentially radicalized recruits, but to create an online environment that is progressively more hostile to anyone targeted by these movements. While the top two tiers are the most visible and draw the most concern, the bottom strata is just as responsible for the rancor, negativity and mis-, dis- and mal- information that clog online spaces, causing a great deal of cumulative harm. This bottom strata includes posting snarky jokes about an unfolding news story, tragedy or controversy; retweeting hoaxes and other misleading narratives ironically, to condemn them, make fun of the people involved or otherwise assert superiority over those who take the narratives seriously; making ambivalent inside jokes because your friends will know what you mean (and for white people in particular, that your friends will know you’re not a real racist); @mentioning the butts of jokes, critiques or collective mocking, thus looping the target of the conversation into the discussion; and easiest of all, jumping into conversations mid-thread without knowing what the issues are.

Just as it does in nature, this omnipresent lower stratum in turn supports all the strata above, including the largest, most dangerous animals at the top of the food chain. Directly and indirectly, insects feed the lions.[19]

Mainstreaming may be a bigger risk than radicalization. Research has shown that media has little direct impact on people’s beliefs, but if it changes what we think other people believe, we will change our attitudes and behaviour to match. If the actions of a loud minority lead to hate being part of a community’s norms and values, it can cause other members of the community – particularly youth – to adopt those attitudes.[20] Mainstreaming can also increase the risk of radicalization because as hate messages become more mainstream, people are more likely to see them and less likely to see pushback and rebuttal of them. In fact, mainstreaming can be imagined as radicalizing an entire community – or even a whole society.

According to journalist and media scholar Daniel Hallin, any topic or idea that might be talked about falls into one of three spheres:

- the sphere of consensus, which contains ideas that are so widely accepted they don’t need to be discussed;

- the sphere of deviance, ideas that are so fully rejected that we don’t need to discuss them;

- and the sphere of legitimate controversy, which includes ideas seen as worth discussing in the media, in polite conversation and political debate.[21]

A lot of hate groups’ effort is focused on moving their messages from the sphere of deviance into one of the two other spheres. Every time someone shares a prejudiced comment or a hateful image, if there’s no action from the platform or pushback from the community, it will eventually enter that community’s sphere of consensus.

Taking their attitudes and ideas from fringe to mainstream is one of the main goals of any hate movement. The networked nature of digital technology makes this much easier, first because anyone can now publish content and distribute it potentially worldwide, and because this network of connections makes it much easier for ideas, attitudes and content to move between platforms and communities. For example, one meme developed on a Reddit forum was repeated on Fox News four days later.[22]

Mainstream media, which still reach the largest audiences (and, in particular, the largest number of voters in most countries) are an essential part of this process as well, particularly when they take the fact that something is being discussed on social media as evidence that it’s newsworthy. As technology columnist Farhad Manjoo put it, “extreme points of views ... that couldn't have been introduced into national discussion in the past are being introduced now by this sort of entry mechanism... people put it on blogs, and then it gets picked up by cable news, and then it becomes a national discussion.”[23]

Similarly, traditional media can play a role in exposing audiences to terms that, when searched, will lead viewers to extremist content. Sometimes this is with the best of intentions: for example, CNN anchor Anderson Cooper asked David Hogg, a survivor of the Parkland school shooting who had become a gun control advocate, about rumours that he was a “crisis actor” paid to take part in a fake event. Not surprisingly, most searches for the term “crisis actor” led to content supporting the conspiracy theory.[24] Other times, though, hate messages spread between media outlets that overlap one another on the ideological spectrum, such as when ideas move from White supremacist forums, to alt-right Twitter and YouTube personalities, to conservative TV commentators, then finally to mainstream TV news.[25]

These hostile environments can also have a direct impact on members of targeted groups. For example, 2SLGBTQ+ youth are almost twice as likely to report having been bullied online as those who are heterosexual.[26] Young people who experience online hate often experience fear, anger, shame and lowered self-esteem.[27] Even those who are accidentally exposed to hate content often feel sad, angry, ashamed or hateful.[28] As a result, members of vulnerable groups may be more reluctant to speak freely online[29] and may feel pressure to hide their identities[30] or to withdraw from online spaces entirely,[31] which has an impact not just on them, but also on the online communities they’re a part of.

Doubt and denialism

As youth overwhelmingly turn to the internet as a source of information, they run the risk of being misled by hate content. If that misinformation is not challenged – and they don’t have the critical thinking skills to challenge it themselves – some youth may come to hold dangerously distorted views. As scholar Jessie Daniels puts it,

“A much more likely and more pernicious risk to young people from hate speech online than either mobilizing or recruiting them into extremist white supremacist groups is… its ability to change how we know what we say we know about issues that have been politically hard won.”[32]

Sowing doubt can serve hate groups’ purposes as well, or better, as outright denialism. Hate groups often appropriate the language of media literacy, saying that they’re engaging in critical thinking when they attack trans people, “just asking questions” when they promote racist pseudoscience and “playing Devil’s advocate” when they diminish how many Jews died in the Holocaust.[33] In this way, hate can harm not just individuals and communities but society itself, by promoting a corrosive cynicism that disengages us from the ways that we actually can make a difference.[34]

[1] Mccauley, C., & Moskalenko, S. (2008). Mechanisms of Political Radicalization: Pathways Toward Terrorism. Terrorism and Political Violence, 20(3), 415-433. doi:10.1080/09546550802073367

[2] Mccauley, C., & Moskalenko, S. (2017). Understanding political radicalization: The two-pyramids model. American Psychologist, 72(3), 205-216. doi:10.1037/amp0000062

[3] Carranco, S., & Milton, J. (2019, April 27). Canada’s new far right: A trove of private chat room messages reveals an extremist subculture. The Globe and Mail. Retrieved from https://www.theglobeandmail.com/canada/article-canadas-new-far-right-a-trove-of-private-chat-room-messages-reveals/

[4] Lewis, B. (2018). Alternative Influence: Broadcasting the Reactionary Right on YouTube (Rep.). Data & Society.

[5] Bergin, A.. Countering Online Radicalisation in Australia. Australian Strategic Policy Institute Forum, 2009.

[6] From Memes to Infowars: How 75 Fascist Activists Were "Red-Pilled". (2018, October 11). Retrieved April 25, 2019, from https://www.bellingcat.com/news/americas/2018/10/11/memes-infowars-75-fascist-activists-red-pilled/

[7] NPR (2018). “How A Rising Star Of White Nationalism Broke Free From The Movement.” Retrieved from https://www.npr.org/transcripts/651052970

[8] Marwick, A., & Lewis, R. (2017). Media manipulation and disinformation online. New York: Data & Society Research Institute.

[9] Quoted in Thakker, P. “Under the Hood of the Right-Wing Media Machine.” Better World. https://betterworld.substack.com/p/under-the-hood-of-the-right-wing-media-machine

[10] Gaudette, T., Scrivens, R., & Venkatesh, V. (2022). The role of the internet in facilitating violent extremism: insights from former right-wing extremists. Terrorism and Political Violence, 34(7), 1339-1356.

[11] Wilson, B. (2022) How young men fall into online radicalization. CBC News.

[12] Kalantzis, D. (2020) What We Get Wrong About Online Radicalization. Vox Pol. https://www.voxpol.eu/what-we-get-wrong-about-online-radicalization/

[13] Amon, K. (2010). Grooming forTerror: the Internet and Young People. Psychiatry, Psychology& Law, 17(3), 424-437.

[14] Evans, R. From Memes to Infowars: How 75 Fascist Activists Were “Red-Pilled”. (2018, October 11). Retrieved April 25, 2019, from https://www.bellingcat.com/news/americas/2018/10/11/memes-infowars-75-fascist-activists-red-pilled/

[15] Gaudette, T., Scrivens, R., & Venkatesh, V. (2022). The role of the internet in facilitating violent extremism: insights from former right-wing extremists. Terrorism and Political Violence, 34(7), 1339-1356.

[16] Carr, J. (2022) The Rise Of Ideologically Motivated Violent Extremism In Canada. Report of the Standing Committee on Public Safety and National Security.

[17] Harvey, J. (2018). Raising white kids: Bringing up children in a racially unjust America. Abingdon Press.

[18] Norman, J. M., & Mikhael, D. (2017, August 28). Youth radicalization is on the rise. Here’s what we know about why. Washington Post. Retrieved September 1, 2017, from https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/monkey-cage/wp/2017/08/25/youth-radicalization-is-on-the-rise-heres-what-we-knowabout-why/?utm_term=.39a485789d43

[19] Milner, R. M., & Phillips, W. (2018, November 20). The Internet Doesn't Need Civility, It Needs Ethics. Retrieved from https://motherboard.vice.com/en_us/article/pa5gxn/the-internet-doesnt-need-civility-it-needs-ethics

[20] Bursztyn, L., Egorov, G., & Fiorin, S. (2020). From extreme to mainstream: The erosion of social norms. American economic review, 110(11), 3522-3548.

[21] Hallin, D. C. (1989). The “Uncensored War”: The Media and Vietnam. New York: Oxford University press. pp. 116–118. ISBN 0-19-503814-2.

[22] Collins, K., & Roose, K. (2018, November 4). Tracing a Meme From the Internet’s Fringe to a Republican Slogan. The New York Times. Retrieved April 26, 2019, from https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2018/11/04/technology/jobs-not-mobs.html

[23] Does the Internet Help or Hurt Democracy [Television series episode]. (2010, June 1). In News Hour. PBS.

[24] Boyd, D. (2019, April 24). The Fragmentation of Truth. Retrieved April 26, 2019, from https://web.archive.org/web/20190425095049/https://points.datasociety.net/the-fragmentation-of-truth-3c766ebb74cf

[25] Daniels, J. (2019, April 9). UN Keynote Speech: Racism in Modern Information and Communication Technologies. Presented to the 10thsession of the Ad Hoc Committee on the Elaboration of Complementary Standards to the International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination. Geneva.

[26] MediaSmarts. (2023). “Young Canadians in a Wireless World, Phase IV: Relationships and Technology - Online Meanness and Cruelty.” MediaSmarts. Ottawa.

[27] Kerr, M., St-Amant M. & McCoy, J. (2022) Don't Click! A Survey of Youth Experiences with Hate & Violent Extremism Online.

[28] Kowalski, K. (2021) How to fight online hate before it leads to violence.

[29] Lenhart, A., Ybarra, M., Zickhur, K., & Price-Feeney, M. (2016). Online Harassment, Digital Abuse, and Cyberstalking in America (Rep.). New York, NY: Data & Society. doi:https://www.datasociety.net/pubs/oh/Online_Harassment_2016.pdf

[30] Joseph, J. (2022) #Blockhate: Centering Survivors and Taking Action on Gendered Online Hate in Canada. YWCA Canada.

[31] Resnick, B. (2017, March 07). The dark psychology of dehumanization, explained. Retrieved from https://www.vox.com/science-and-health/2017/3/7/14456154/dehumanization-psychology-explained

[32] Daniels, J. (2008). Race, civil rights, and hate speech in the digital era.

[33] Fister, B. (2021) Lizard People in the Library. Project Information Literacy. https://projectinfolit.org/pubs/provocation-series/essays/lizard-people-in-the-library.html

[34] Neiwert, D. (2020). Red pill, blue pill: How to counteract the conspiracy theories that are killing us. Rowman & Littlefield.