Companion reading

Authenticating online information can be like doing detective work, in that you’re trying to “piece the story” together by gathering clues. In general, the more clues you gather, the more confident you can be in your ultimate determination. Conversely, the more important it is for you to know if something is reliable, the more clues you’ll need.

That’s why we need to give up on the idea that we can “trust our gut” when trying to verify information or tell if a source is reliable. Often, the most important clues come from outside the source itself.

For example, consider this video:

Is it true or false? There’s really no way to be sure just by looking at it. You have to look at who uploaded it and do some additional research to find out that while the video is real, it’s not truthful: the clam is not “licking” (that’s actually its foot, not a tongue) and the salt is irrelevant (it’s actually trying to drag itself back into water before it suffocates).

Companion reading doesn’t mean doubting or questioning everything. It means asking key questions that help you evaluate how reliable a piece of information might be. You may not be able to find out definitively if something is true or not, and even the term “true” can be a complicated one – it’s not unusual for something that’s real to be used in a misleading context (such as an old photo being misrepresented as new).

- Your first question, then, is How sure do I need to be? Are you (or someone else) going to base an important decision on this information? Could people be helped by this information if it’s good or harmed if it’s bad? The answer to this is going to determine how much work you put into answering the questions that follow.

Your second question should be Has someone else debunked this already? Doing a search for the subject with the words “hoax” or “fake” or using a fact-checking site can save you a lot of time.

- You can use a specific fact-checker website like Snopes.com, or use MediaSmarts’ fact-checking search engine, which searches more than a dozen fact-checkers including Snopes, Agence France Presse Canada, FactCheck.org, Politifact, the Associated Press Fact Check, HoaxEye and Les Decrypteurs.

- If you want to use a different fact-checker, make sure it’s signed on to the International Fact-Checking Network’s code of principles (see https://ifcncodeofprinciples.poynter.org/signatories).

Remember that just because a fact-checker hasn’t debunked something doesn’t mean it’s true. It can take a while for fact-checkers to verify a story, and not every one will verify every story.

- You can use a specific fact-checker website like Snopes.com, or use MediaSmarts’ fact-checking search engine, which searches more than a dozen fact-checkers including Snopes, Agence France Presse Canada, FactCheck.org, Politifact, the Associated Press Fact Check, HoaxEye and Les Decrypteurs.

- It’s important to ask What is the original source of this information? Because of the networked nature of the internet, much of the information we find comes to us second-hand or at an even greater remove. We have to make an extra effort to identify its origin: one study found that while “about half of the people in [their] experiment could recall who had shared the post … only about 2 in 10 could remember the source of the article.”[1] Before you can evaluate any information, you need to find out where it originated. Did the source generate or publish the information itself? If not, does it give links or citations to the original source? You can’t decide whether it came from a reliable source until you know what that source actually was.[2]

The easiest way to find the source is usually to follow links that will lead you to the original story. On social media, like Facebook, the link is usually at the end or bottom of the post. On a website, follow links that lead back to the source. Look for phrases like “According to” a source, a source “reported” or the word “Source” at the top or bottom of a story. Make sure to keep going until you’re sure you’re at the original!

If there are no links or sources, you can also use a search engine like Google or DuckDuckGo to find the original source of the claim or story. Keep looking until you find a source that you know is reliable. If you’ve been looking for a few minutes and you can’t find it covered by any reliable sources, consider it unverified for now.

- Once you’ve found where the information came from, you can now ask Can I trust this source?[3] Don't rely too much on how official or professional a site looks – while misspellings and other errors can be a sign that something is unreliable, many misinformation sites look just as professional as legitimate ones.

To find out if a source is reliable, ask these three questions:

- Do they really exist?

It’s easy to make fake pictures, websites and social network profiles that look just as real and professional as anything out there. “About Us” pages and profiles are easy to fake, so use Wikipedia or a search engine like Google to find out if other people say they really exist.

- Put quotation marks around it to make sure that related words are searched together (e.g. “New York Times”) and exclude results from the source by using the minus sign (e.g. -www.nytimes.com). Doing a search for “RT” and adding -www.rt.com, for instance, gives you results that describe it as “a Russian propaganda channel” and show that it has registered as a “foreign agent” in the U.S., while searching for “Reuters” and adding -www.reuters.com tells you that it is a news agency that supplies stories to newspapers around the world. Make sure to go past the first page of results, and don’t assume that the order of results tells you anything about how reliable they are![4]

- Pay attention to things that are hard to fake. For example, if somebody claims to work for a particular company, check the company’s website or do a search for their name and the company’s name to see if they’ve ever been mentioned together in reliable sources (like a newspaper you already know is real).

- Are they who they say they are?

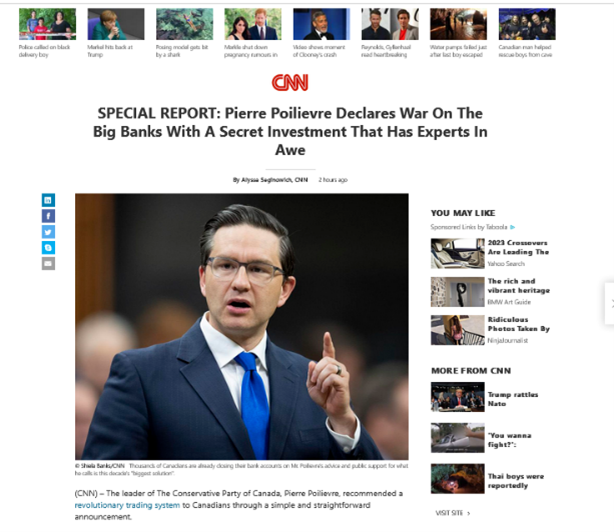

It’s easy to pretend to be someone else online, so once you know the source really exists, you need to find out if what you’re looking at really came from them. For example, this scam relies on you believing that you’re on the real CNN website. Double-check that the web address you’ve been looking at is the actual web address for this source. If you’re not sure, do a search for the organization or check Wikipedia to find the real web address. You can also do that to double-check that an organization’s social media account is for real. (Verified accounts on Instagram still mean that the person or organization is who they say they are, but on X – formerly Twitter – it now only means they’ve paid for a blue check mark.)

It’s easy to pretend to be someone else online, so once you know the source really exists, you need to find out if what you’re looking at really came from them. For example, this scam relies on you believing that you’re on the real CNN website. Double-check that the web address you’ve been looking at is the actual web address for this source. If you’re not sure, do a search for the organization or check Wikipedia to find the real web address. You can also do that to double-check that an organization’s social media account is for real. (Verified accounts on Instagram still mean that the person or organization is who they say they are, but on X – formerly Twitter – it now only means they’ve paid for a blue check mark.)

- Are they trustworthy?

- For sources of general information, like newspapers, that means asking if they have a process for making sure they’re giving you good information, and a good track record of doing it. How often do they make mistakes? If they do make mistakes, do they admit them and publish corrections?

- See if you can find out who pays for or sponsors the source. Will they make money if you believe them? Are they pushing a particular opinion or political position? Are they willing to publish things their owners, or their readers, wouldn’t agree with?

- For more specialized sources, you want to ask whether they’re experts or authorities on that topic. Are they generally considered to be reliable? Do they have a generally recognized bias towards one view or another? (That doesn’t automatically make them unreliable, but it does help you view the information more skeptically.)

- When asking this question, keep in mind that not all sources are “playing fair”: misinformation is often spread online in order to sell you something, to get you mad about something or just as a joke. Some of them use names that sound like legitimate outlets, such as the Lansing Sun or the Ann Arbor Times,[5] and count on you not double-checking. That’s why it’s essential to find out something about the source’s “track record.” Here are some common forms of intentional misinformation:

- Hoaxes and false news: These are spread on purpose to mislead people. Sometimes these are motivated by malicious or mischievous intent; sometimes they’re motivated for ideological or political purposes; other times they’re done for financial gain.

- Scams: Sometimes the purpose of a fake story is to separate you from your money, to get you to give up your personal information or to get you to click on a link that will download malware onto your computer.

- Ads: Some things that are spread around are obviously ads, but others are disguised as “real” content.

- Do they really exist?

- Another approach is to check other sources that you already know are reliable. This step may sometimes be the last one you do, but it could also be the first, since it gives you a sense of whether legitimate sources are covering a claim or story. By taking this step, you can be sure you get the whole story. Remember, all sources make mistakes sometimes, but reliable ones will correct them.

Looking at other sources can help you find out if the first place you saw something might have been leaving something out. This is also a good way of discovering any possible bias that might exist in any one source.

- The News tab is better than the main Google search for this step because it only shows real news sources. While not every source that’s included is perfectly reliable, they’re all news outlets that really exist.

- You can also use our custom news search, tiny.cc/news-search, which searches Canadian and international sources of reliable news.

- The News tab is better than the main Google search for this step because it only shows real news sources. While not every source that’s included is perfectly reliable, they’re all news outlets that really exist.

- You can also use this step to find out whether something agrees with what most experts on that topic think – what’s called the consensus view. While it’s generally good reporting to give both sides of a story, including views that experts agree aren’t right can result in spreading misinformation.

- Our custom search, mediasmarts.ca/science-search, can help you find the consensus on specialist topics like science and medicine.

Use Control-F (Command-F on a Mac) to quickly search a website for a word or phrase.

Deepfakes and chatbots

Generative AI can produce both misinformation and intentional disinformation. Unfortunately, just warning people about the risk of AI disinformation doesn’t help them spot it. In fact, it makes them more likely to think that real content is fake.[6]

Don’t rely on evidence from inside an image or video itself (like extra fingers). Image generators’ ability to correct these is improving quickly, and if we want to debunk a photo it’s easy to see “evidence” that isn’t really there suggesting it’s fake.

Instead, use companion reading skills. For example, using a reverse image search like Tineye can tell you quickly where a photo first appeared. That may not tell you if it’s a deepfake, but if it didn’t come from a reliable source, there’s no reason to believe it’s real.

- On a mobile device, you can do a reverse image search using the Chrome browser. Press and hold on the image, then tap Search Google for This Image.

Consulting fact-checkers and sources that you already know to be reliable (like legitimate news outlets) can also help sort fact from AI-fiction.

[1] Sterret, D., Malato, D., Benz, J., Kantor, L., Tompson, T., Rosenstiel, T., ... & Swanson, E. (2018). Who shared it? How Americans decide what news to trust on social media. NORC Working Paper Series WP-2018-001.

[2] Wineburg, Sam and Sarah McGrew. “Lateral Reading: Reading Less and Learning More When Evaluating Digital Information.” Stanford History Education Group, September 2017.

[3] Guess, A., McGregor, S., Pennycook, G., & Rand, D. (2024). Unbundling Digital Media Literacy Tips: Results from Two Experiments.

[4] Wineburg, Sam and Sarah McGrew. “Lateral Reading: Reading Less and Learning More When Evaluating Digital Information.” Stanford History Education Group, September 2017.

[5] Thompson, C. (2019) Dozens of new websites appear to be Michigan local news outlets, but with political bent. Lansing State Journal.

[6] Ternovski, J., Kalla, J., & Aronow, P. (2022). The negative consequences of informing voters about deepfakes: evidence from two survey experiments. Journal of Online Trust and Safety, 1(2).