Impact of Media on Body Image

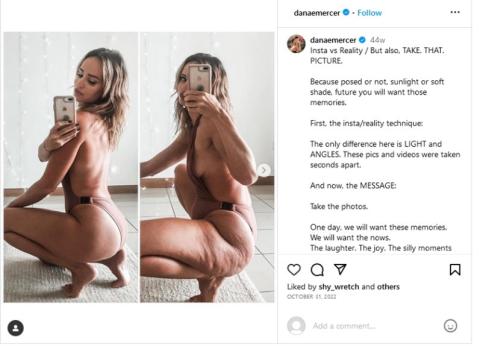

Though they are by no means the only factor, media representations of weight and body shape are a major element in body image concerns. Media of all kinds frequently promote weight stigma, most often representing weight as an individual responsibility.[1] Time spent on social media and watching television[2] and exposure to manipulated photos on social media[3] have all been linked to negative body image or increased concern with appearance.

As well, the other two factors identified in the Tripartite Influence Model[4] – parents and peers – mean that even if young people’s body image isn’t directly affected by media, it may be affected by what they think other people believe.[5] For instance, one study found that while social media was linked to lower body satisfaction, it did so only when it led users to compare themselves to others.[6]

Traditionally seen as more of a girls’ issue, a growing body of research has emerged exploring body image and boys. An Australian study revealed that body image issues in men were related to a lower quality of life in men as well as women.[7]

Girls

Images of female bodies are everywhere, with women and girls – and their body parts – selling everything from food to cars. Popular film and television actresses are becoming younger, taller and thinner. Women’s magazines are full of articles urging that if you can just lose those last twenty pounds, you will have it all: the perfect marriage, loving children, great sex and a rewarding career. The age of Snapchat, TikTok and Instagram has perpetuated the notion that to have the ideal life you must have the ideal body type.

Why are these impossible standards of beauty being imposed on girls, the majority of whom look nothing like the models that are being presented to them? Some of the causes are economic: by presenting a physical ideal that is difficult to achieve and maintain, the cosmetic and diet industries are assured continual growth and profits. It’s estimated that the diet industry alone brings in $224 billion (U.S.) a year selling temporary weight loss,[8] with 80 percent of dieters regaining their lost weight.[9] Marketers know that girls and women who are insecure about their bodies are more likely to buy beauty products, new clothes and diet aids. This business strategy has worked over the ages, as nine in 10 girls now say they’re unhappy with their bodies due to this perfectionist culture.[10]

Why are these impossible standards of beauty being imposed on girls, the majority of whom look nothing like the models that are being presented to them? Some of the causes are economic: by presenting a physical ideal that is difficult to achieve and maintain, the cosmetic and diet industries are assured continual growth and profits. It’s estimated that the diet industry alone brings in $224 billion (U.S.) a year selling temporary weight loss,[8] with 80 percent of dieters regaining their lost weight.[9] Marketers know that girls and women who are insecure about their bodies are more likely to buy beauty products, new clothes and diet aids. This business strategy has worked over the ages, as nine in 10 girls now say they’re unhappy with their bodies due to this perfectionist culture.[10]

These messages are so powerful and widespread in our culture that they affect girls long before they’re exposed to fashion or beauty ads or magazines. Three-year-olds already prefer game pieces that depict thin people over those representing heavier ones.[11] Girls are also becoming exposed to beauty messages more easily through access to social media on their personal electronic devices. The need to constantly be tuned into social media allows messages about the need “to have a picture-perfect life” and “to look pretty all the time” to infiltrate every part of their lives.[12]

The effects of exposure to these images and messages goes beyond influencing girls to buy diet and beauty products. Exposure to images of thin, young, photoshopped female bodies is linked to anxiety, depression, loss of self-esteem and body dissatisfaction in girls and young women.[13]

As media activist Jean Kilbourne puts it, “women are sold to the diet industry by the magazines we read and the television programs we watch, almost all of which make us feel anxious about our weight.”[14] The barrage of messages about thinness, dieting and beauty tells “ordinary” girls that they’re always in need of adjustment—and that the female body is an object to be perfected. In some cases, this can be a factor in girls developing eating disorders and a barrier to recovering from them. Dr. Robbie Campbell, professor of psychiatry at Western University, points out that while multiple factors contribute to eating disorders, “the media is driving the one thing that seems to keep it in front of us all the time… the media serves as a constant trigger as we’re trying to move these girls towards wellness.”[15] Media representations of eating disorders, however, may also be partially responsible for the misconception that they’re only experienced by thin people: in fact, a study of Canadian teens found less than six percent of those with eating disorders had a Body Mass Index in the “underweight” range.[16]

As media activist Jean Kilbourne puts it, “women are sold to the diet industry by the magazines we read and the television programs we watch, almost all of which make us feel anxious about our weight.”[14] The barrage of messages about thinness, dieting and beauty tells “ordinary” girls that they’re always in need of adjustment—and that the female body is an object to be perfected. In some cases, this can be a factor in girls developing eating disorders and a barrier to recovering from them. Dr. Robbie Campbell, professor of psychiatry at Western University, points out that while multiple factors contribute to eating disorders, “the media is driving the one thing that seems to keep it in front of us all the time… the media serves as a constant trigger as we’re trying to move these girls towards wellness.”[15] Media representations of eating disorders, however, may also be partially responsible for the misconception that they’re only experienced by thin people: in fact, a study of Canadian teens found less than six percent of those with eating disorders had a Body Mass Index in the “underweight” range.[16]

Kilbourne argues that the overwhelming presence of media images of painfully thin women means that real girls’ bodies have become invisible in the mass media. The real tragedy, Kilbourne concludes, is that many girls internalize these stereotypes and judge themselves by the beauty industry’s standards. This focus on beauty and desirability “effectively destroys any awareness and action that might help to change that climate.”[17]

Given the serious potential consequences, it’s essential that girls and young women develop a critical understanding of the constructed nature of media representations of women’s bodies on all platforms and the reasons why these images are perpetuated. More importantly, they need to be empowered to challenge these representations and advocate for more realistic representations. Because girls’ exposure to these messages starts so young, it’s also vital that this education starts at an early age.

Boys

Traditionally, most of the concerns about media and body image have revolved around girls, but more and more, researchers and health professionals are turning their attention to boys, as well. A growing body also experience anxiety about their bodies. One recent study found that one in four Canadian youth are at risk of developing muscle dysmorphia, in which the desire for a muscular body drives them to unhealthy extremes.[18]

While media images of the ideal female body may change over time, it is only relatively recently that men’s bodies have been idealized in mass media at all – and even more recently that an ideal male body was considered necessary for stardom. As writer Elamin Abdelmahmoud put it, “Harrison Ford didn’t need abs to electrify audiences, and neither did Bruce Willis. They looked fit, sure, but part of the appeal was that they also looked like regular guys.”[19] Now, though, even actors who get their starts in comedy, such as Kumail Nanjiani and John Krasinski, need impossible physiques: “for male actors… getting a part in action and especially superhero movies is the way to become a star. With a few rare exceptions, that means your body has to look superheroic.”[20]

Cultural expectations that guys have to be nonchalant when it comes to their physiques makes body dissatisfaction in boys more difficult to assess, but there is little doubt that they’re affected by media representations of idealized masculinity. As social media has made youth more active media makers, as well as consumers, boys have become more conscious of their own appearance. As one of the participants in MediaSmarts’ study To Share or Not to Share put it, “for guys especially, it’s better if you take a photo with that light to show that you have a jawline.”[21]

As advertisers increasingly turn their attention to young men as a lucrative demographic, it’s unlikely that such representations are going to disappear any time soon. Other research has found a relationship between the increase in idealized male bodies in media and the rise in body dissatisfaction and weight disorders in boys and young men. A 2017 study, for instance, concluded that messages men are seeing online contribute to their body dissatisfaction because they promote rigid exercise and dietary practices aimed at producing the ideal muscular physique.[22] As Jennifer Mills, associate professor of clinical psychology at York University, put it, “the average man is comparing himself to a hyper-muscular, very lean body type and is going to make him feel worse about his own body because he does not live up to that ideal.”[23]

Body dissatisfaction amongst boys and young men is fuelled not just by the idealized male bodies they see in media, but also by the idealized images of women that are represented. One study found that young men were more self-conscious about their bodies after seeing photos of sexualized, scantily-clad women, based on the belief that girls would expect similar idealized physiques from men as well.[24]

A 2020 study found that a third of boys aged 11-17 had seen content online encouraging them to “bulk up.”[25] This obsession may take the form of fixation with exercise, particularly weightlifting; abuse of anabolic steroids and other performance-enhancing drugs, which may damage the heart, liver, kidneys and immune system; and muscle dysmorphia, whose sufferers see themselves as thin and weak no matter how well-muscled they become.[26]

A 2020 study found that a third of boys aged 11-17 had seen content online encouraging them to “bulk up.”[25] This obsession may take the form of fixation with exercise, particularly weightlifting; abuse of anabolic steroids and other performance-enhancing drugs, which may damage the heart, liver, kidneys and immune system; and muscle dysmorphia, whose sufferers see themselves as thin and weak no matter how well-muscled they become.[26]

While the desire to be more muscular has been the focus in most of the research on body image issues among boys, recent evidence suggests that rather than focusing on building muscle mass, boys are most likely to focus on achieving or maintaining an average weight that is neither over- nor underweight, to avoid standing out from their peers.[27] As a result, boys who are unhappy with their bodies are almost equally likely to be concerned about being too thin as being too fat.[28] This suggests that the level of eating disorders and other body image issues may be higher than is currently thought, since researchers have traditionally measured body dissatisfaction in boys based on their desire for a more muscular build. It also suggests that interventions based on those that have been designed for girls may be less effective with boys. For instance, researchers found that Body Talk in the Digital Age, a classroom program designed to help youth deal with body image issues, had positive results with girls but not with boys.[29]

This may be because while girls are typically open about being concerned with their bodies in general and weight in particular, boys are under pressure to avoid being too skinny or heavy while also under pressure to appear indifferent about how they look.[30] Julia Taylor, a counselor at a North Carolina high school and author of Perfectly You, describes her experience at a body image awareness event: “Guys did not even want to go near our table,” she says, but when she left the table boys “would look at it, then walk away, then come back and fold up a pamphlet real quickly and put it in their pocket.”[31] Parents, teachers and counselors need to be more aware of the prevalence of body image issues among boys and not wait for them to openly seek help.[32]

While boys need to be educated and provided with the same sorts of tools as girls, they also need materials that are specifically designed for them.[33] These materials should address their particular concerns, including the drive to muscularity and the pressure to fit in among peers, while also being accessible to boys in a private space.

Trans, non-binary and gender non-conforming youth

“We need more representations of bodies - trans, queer, Black, curvy, disabled.”[34]

Young people who are trans, non-binary or gender non-conforming also experience body image issues. While relatively little research has been done specifically regarding these groups and body image,[35] what has been done suggests that they typically experience effects similar to those of other genders.[36]

These may be made more complex by how rarely they are represented in media, and by the narrow range of non-binary bodies – nearly always thin, White, and androgynous – portrayed when they do appear.[37] While trans youth are likely to become more satisfied with their bodies over the process of gender affirmation, they also frequently engage in risky behaviours such as using laxatives and extreme dietary restrictions,[38] and they often find that gender dysphoria and other body image issues are entangled and make each other worse.[39]

Resources that address body image issues, however, are beginning to recognize the intersections between them and gender identity: for example, A Smart Girl’s Guide: Body Image Book, a book on body image published by American Girl, includes trans and non-binary identities and encourages kids to talk to a trusted adult about their relationships with their bodies.[40]

As well, there is some evidence that unlike cisgender youth, trans and non-binary young people may experience positive effects on their body image as a result of using digital media specifically. Though the reasons for this are not yet clear, one explanation may be that "digital media offers the opportunity to represent oneself using chosen names, pronouns, and selected photographs that may simplify this process compared with offline communities, with different platforms facilitating this in different ways.”[41]

If you or someone you know needs support in dealing with an eating disorder, visit the National Eating Disorder Information Centre.

[1] Kite, J., Huang, B. H., Laird, Y., Grunseit, A., McGill, B., Williams, K., ... & Thomas, M. (2022). Influence and effects of weight stigmatisation in media: A systematic review. Clinical Medicine, 48.

[2] Kowal, M., Sorokowski, P., Pisanski, K., Valentova, J. V., Varella, M. A., Frederick, D. A., ... & Mišetić, K. (2022). Predictors of enhancing human physical attractiveness: Data from 93 countries. Evolution and Human Behavior, 43(6), 455-474.

[3] Kleemans, M., Daalmans, S., Carbaat, I., & Anschütz, D. (2018). Picture perfect: The direct effect of manipulated Instagram photos on body image in adolescent girls. Media Psychology, 21(1), 93-110.

[4] Sole-Smith, V. (2023). Fat talk: parenting in the age of diet culture. First edition. New York, Henry Holt and Company.

[5] Valkenburg, P. M., Peter, J., & Walther, J. B. (2016). Media effects: Theory and research. Annual review of psychology, 67, 315-338.

[6] Jarman, H. K., McLean, S. A., Slater, A., Marques, M. D., & Paxton, S. J. (2021). Direct and indirect relationships between social media use and body satisfaction: A prospective study among adolescent boys and girls. New Media & Society, 14614448211058468.

[7] Griffiths, S. et al (2016) Sex differences in the relationships between body dissatisfaction, quality of life and psychological distress. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Public Health, 40(6). 518-522.

[8] Weight Loss and Weight Management Market Size, Share, Growth Analysis Report By Diet (Meal, Supplement, and Beverage), By Service (Fitness Centers, Consulting Services, Slimming Centers, and Online Programs), and By Region - Global and Regional Industry Insights, Overview, Comprehensive Analysis, Trends, Statistical Research, Market Intelligence, Historical Data and Forecast 2022 – 2030. (2022) Facts and Figures. https://www.fnfresearch.com/weight-loss-and-weight-management-market

[9] Priya Sumithran, Luke A. Prendergast, Elizabeth Delbridge, Katrina Purcell, Arthur Shulkes, Adamandia Kriketos, Joseph Proietto. Long-Term Persistence of Hormonal Adaptations to Weight

[10] Royal Society for Public Health. (2017, May) Status of mind: Social media and young people’s mental health and wellbeing. Retrieved from https://www.rsph.org.uk/static/uploaded/d125b27c-0b62-41c5-a2c0155a8887cd01.pdf

[11] (Harriger, J.A., Calogero, R.M., Witherington, D.C., & Smith J.E. (2010). Body size stereotyping and internalization of the thin-ideal in preschool-age girls. Sex Roles, 63, 609-620. doi: 10.1007/s11199-010-9868-1)

[12] Girl Guiding UK. Girls Attitude Survey. 2019.

[13] Sherlock, M., & Wagstaff, D. L. (2019). Exploring the relationship between frequency of Instagram use, exposure to idealized images, and psychological well-being in women. Psychology of Popular Media Culture, 8(4), 482–490. https://doi.org/10.1037/ppm0000182

[14] Kilbourne, Jean. Can’t Buy My Love: How Advertising Changes the Way We Think and Feel. Touchstone, 2000.

[15] Gollom, Mark. “Vogue ban of too-thin models a ‘huge’ step.” CBC News, May 4, 2012. <https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/vogue-ban-of-too-thin-models-a-huge-step-1.1195703>

[16] Flament, M. F., Henderson, K., Buchholz, A., Obeid, N., Nguyen, H. N., Birmingham, M., & Goldfield, G. (2015). Weight status and DSM-5 diagnoses of eating disorders in adolescents from the community. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 54(5), 403-411.

[17] Kilbourne, 2000.

[18] Ganson, K. T., Hallward, L., Cunningham, M. L., Rodgers, R. F., DClinPsych, S. B. M., & Nagata, J. M. (2023). Muscle dysmorphia symptomatology among a national sample of Canadian adolescents and young adults. Body Image, 44, 178-186..

[19] Abdelahmoud, E. (2021) “This is What it’s Like for Men with Eating Disorders.” Buzzfeed. https://www.buzzfeednews.com/article/elaminabdelmahmoud/male-eating-disorders-overexercise-body-image-diet?ref=bfnsplash

[20] Abed-Santos, A. (2021) “The open secret to looking like a superhero.” Vox. https://www.vox.com/the-goods/22760163/steroids-hgh-hollywood-actors-peds-performance-enhancing-drugs

[21] Johnson, M., Steeves, V., Shade, L.R, Foran, G. (2017) To Share or Not to Share: How Teens Make Privacy Decisions on Social Media.

[22] Carrotte, E.R, Prichard, I., Su Cheng Lim, M. (2017) Fitspiration on social media: A content analysis of gendered images. Journal of Medical Research 19(3).

[23] Quoted in Khan, A. (2022) “How these men are overcoming social media-fuelled body image mental health challenges.” Global News. https://globalnews.ca/news/8468688/men-body-image-socia-media/

[24] Field, A., Sonneville, K., Crosby, R. (2014) Prospective Associations of Concerns About Physique and the Development of Obesity, binge drinking, and drug use among adolescent boys and young adult men. JAMA Pediatrics 168(1). 34-39.

[25] Katz, A & El Asam, Aiman. (2020) In Their Own Words: The Digital Lives of Schoolchildren. Internet Matters. https://www.internetmatters.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/Internet-Matters-CyberSurvey19-Digital-Life-Web.pdf

[26] Kurtz, Sara. Adolescent Boys’ and Girls’ Perceived Body Image and the Influence of Media: The Impact of Media Literacy Education on Adolescents Body Dissatisfaction. Carroll University, December 2010.

[27] S. Bryn Austin, Jess Haines, Paul J. Veugelers. Body satisfaction and body weight: gender differences and sociodemographic determinants. BMC Public Health 2009, 9:313.)

[28] Freeman et al. (2012). The Health of Canada’s Young People: A Mental Health Focus. Public Health Agency of Canada.

[29] Bell, B. T., Taylor, C., Paddock, D. L., Bates, A., & Orange, S. T. (2021). Body talk in the digital age: A controlled evaluation of a classroom-based intervention to reduce appearance commentary and improve body image. Health Psychology Open, 8(1), 20551029211018920.

[30] Norman, Moss. Embodying the Double-Bind of Masculinity: Young Men and Discourses of Normalcy, Health, Heterosexuality, and Individualism. Men and Masculinities, Sept 17 2011

[31] Grace Rubinstein. Boys and Body Image: Eating Disorders Don’t Discriminate. Edutopia, April 2010.

[32] Ibid.

[33] McCabe, M.P., Ricciardili, L.A. (2006). A prospective study of extreme weight change behaviors among adolescent boys and girls. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 35(3), 425-434.

[34] Quoted in Women and Equalities Committee (2020). Body Image Survey Results. https://publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm5801/cmselect/cmwomeq/805/80502.htm

[35] Heiden-Rootes, K., Linsenmeyer, W., Levine, S., Oliveras, M., & Joseph, M. (2023). A scoping review of the research literature on eating and body image for transgender and nonbinary adults. Journal of Eating Disorders, 11(1), 111.

[36] Shaheen, A., Kumar, H., Dev, W., Parkash, O., & Rai, K. (2016). Gender difference regarding body image: A comparative study. Advances in Obesity, Weight Management & Control, 4(4), 76-79.

[37] Ifrach, M.R. (2022) Body Image, Perception and Health Beyond the Binary. National LGBTQIA+ Health Education Center. https://www.lgbtqiahealtheducation.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/Body-Image-Perception-and-Health-Beyond.pdf

[38] Brewer, G., Hanson, L., & Caswell, N. (2022). Body image and eating behavior in transgender men and women: The importance of stage of gender affirmation. Bulletin of Applied Transgender Studies, 1(1-2), 71-95.

[39] Cusack, C. E., Iampieri, A. O., & Galupo, M. P. (2022). “I’m still not sure if the eating disorder is a result of gender dysphoria”: Trans and nonbinary individuals’ descriptions of their eating and body concerns in relation to their gender. Psychology of sexual orientation and gender diversity.

[40] Battinger, B. (2022) American Girl sticks by LGBTQ+ identities in body image book despite boycott threats. The Sacramento Bee.

[41] Allen, B. J., Stratman, Z. E., Kerr, B. R., Zhao, Q., & Moreno, M. A. (2021). Associations between psychosocial measures and digital media use among transgender youth: Cross-sectional study. JMIR pediatrics and parenting, 4(3), e25801.