Indigenous expression in the arts and media

Passing on information orally was possible when the traditional languages were still very much alive, which is no longer true today. As of 2017, Statistics Canada reported that there were 40 Indigenous languages spoken by 500 or fewer people.[1]

Some nations, like the Huron-Wendat nation in Quebec, are working with academic researchers to revitalize and relearn their languages. Traditionally, written communication was not necessary for the survival of the language. Stories told by extraordinary storytellers could easily occupy long winter evenings and bring entire communities together. Today, things are very different: digital and satellite TV, telephones, the internet, social networks and video games have created new social relationships across all societies, including Indigenous ones.

These new social relationships are prompted by searches for fast, effective communication. A Cree person isolated in Northern Quebec can communicate and share their lifestyle with a single person or thousands living on the other side of the world. Armed with a video camera, they can interview Elders, recording and preserving their stories and accounts for posterity. A recorded form of communication makes possible what an oral form cannot: saving, protecting and preserving a culture that would otherwise be in danger of disappearing.

While in the past, mass media has been seen as a main contributor to the erosion of the cultural foundations of Indigenous societies, the ability to use digital technology to record, create and distribute media makes it an essential tool for developing and sharing new forms of expression and for preserving language, culture and identity. As the report on the National Inquiry on Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls puts it, “for fair media representation of Indigenous women, girls, and 2SLGBTQ+ people, Indigenous Peoples must be able to tell their own stories. Indigenous Peoples are the experts of their own lives, and their knowledge should be represented in the media.”[2]

As part of this process, Indigenous artists have been using film, music and other media to preserve and promote their language and culture. SG̲aawaay Ḵ’uuna, a movie fully filmed in Haida – a language with fewer than 30 fluent speakers – is a powerful document of the culture and language of that people that can reach young people in a way that other media can’t. Benjamin Young, a consultant on the film, said that “film is the most valuable medium that we have out there, the most attractive, the one that really sticks. I think any youth, especially Haida youth, that sees their language being spoken on a feature-length film – that will affirm their identities and empower them to speak.”[3] Children’s media can play a similar role: the APTN animated series Lil Glooscap and the legends of Turtle Island was recorded in English, French and Wolastoqey, an Indigenous language with 350 known speakers.[4]

TV, film and theatre

Many Indigenous people found empowerment in reappropriating various forms of artistic expression during the last 25 years of the 20th century. Since the 1970s, in line with the political affirmation of Indigenous people at the national and international levels, theatre, literature, music and filmmaking have become vital forms of expression among First Nations and the Inuit in Canada. These are but a few examples of the extraordinary vitality of the Indigenous arts. In the mid-1980s, The Rez Sisters by Tomson Highway and Yves Sioui Durand’s founding of the Ondinnok troupe marked the arrival of Indigenous theatre on the Canadian stage. Indigenous writers like Lee Maracle and Richard Wagamese made their mark in the publishing industry. Wholly Indigenous publishing houses like Pemmican Publications and Theytus Books demonstrate that media control and large distribution go hand in hand, while comics such as Cole Pauls’ Dakwäkãda Warriors bring Indigenous culture and language into the graphic novel form.[5] In the 1990s, successful CBC series like North of 60 and The Rez earned Tom Jackson and Tina Keeper spots as TV media personalities; today actors such as Letterkenny’s Kaniehtiio Horn and Cara Gee of The Expanse are breaking new ground in terms of the authenticity and variety of the roles they play, while series such as Molly of Denali, Wolf Joe and Coyote’s Crazy Smart Science Show allow Indigenous youth to see themselves represented onscreen

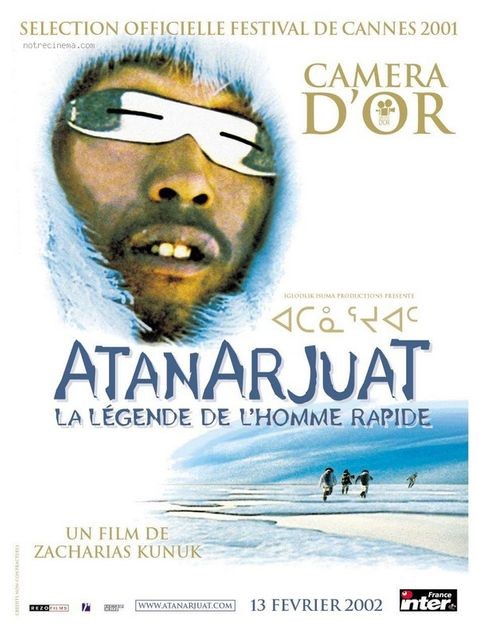

For many Indigenous people, documentary filmmaking is also becoming a preferred form of expression. Alanis Obomsawin, to whom we owe Kanehsatake: 270 Years of Resistance, a film about the Oka crisis, is one of the most internationally well-known of these filmmakers. The founding of the First Peoples’ Festival Présence autochtone in Montreal in 1990 has made it possible for Indigenous cinema to take advantage of significant media coverage. A final barrier was overcome when Atanarjuat (The Fast Runner), a film by Inuit director Zacharias Kunuk, won the Caméra d’or for best first film at the 2001 International Cannes Festival and was very successful in movie theatres throughout Canada. More recently, the CBC film series Keep Calm and Decolonize features a mix of documentary and fiction films by Indigenous artists responding to Buffy Sainte-Marie’s call to “imagine new ways forward” following the 150th anniversary of Confederation.[6]

For many Indigenous people, documentary filmmaking is also becoming a preferred form of expression. Alanis Obomsawin, to whom we owe Kanehsatake: 270 Years of Resistance, a film about the Oka crisis, is one of the most internationally well-known of these filmmakers. The founding of the First Peoples’ Festival Présence autochtone in Montreal in 1990 has made it possible for Indigenous cinema to take advantage of significant media coverage. A final barrier was overcome when Atanarjuat (The Fast Runner), a film by Inuit director Zacharias Kunuk, won the Caméra d’or for best first film at the 2001 International Cannes Festival and was very successful in movie theatres throughout Canada. More recently, the CBC film series Keep Calm and Decolonize features a mix of documentary and fiction films by Indigenous artists responding to Buffy Sainte-Marie’s call to “imagine new ways forward” following the 150th anniversary of Confederation.[6]

Since 2004, Wapikoni Mobile, a travelling cinema studio founded by Manon Barbeau, has been making it possible to reach Indigenous youth throughout Quebec by helping them learn filmmaking techniques through training. Similarly, N’We Jinan, a Montreal-based non-profit, trains Indigenous teens to make their own music and videos,[7] while the Mi’kmaw Radio Rookies program trains Indigenous youth in Nova Scotia to tell their own stories in audio format.[8]

Music and radio

Fortunately, “exotic” songs like Halfbreed and Running Bear are now a thing of the past. It is now the Indigenous musicians’ turn to evoke day-to-day living in their communities, their suffering and their successes. With help from the Broadcasting Act, which requires that at least 35 percent of the music broadcast by radio stations be Canadian, singers like Buffy Sainte-Marie, Susan Aglukark and Florent Vollant have been critically acclaimed and largely adopted by the mainstream public. They have contributed to opening up the way for a new generation of Indigenous singers and musicians. The success of artists such as Tanya Tagaq, A Tribe Called Red and Snotty Nose Rez Kids shows that Indigenous musicians have become much more widely known in Canada.

As one Indigenous musician put it, “there is a certain openness to the presence of Indigenous artists. We used to be seen as exotic and different twenty years ago, but now there’s a greater awareness or willingness to accept Indigenous artists.”[9] According to Indigenous sociologist Guy Sioui Durand, musical production in an Indigenous context today is often a form of social engagement, with young artists expressing themselves less through overtly political issues and opinions and much more through messages of hope.[10]

Digital media

The internet is proving to be a powerful tool for sharing and promoting Indigenous culture. The Premières Nations online magazine is a means of expression through the Web and a window into the First Nations world. Land InSIGHTS devotes a full page to Indigenous visual arts.

Social media have also become valuable as a way for Indigenous people to share their own experiences directly and to connect and organize for social action[11] – as was demonstrated by the success of the #IdleNoMore campaign to draw mainstream media attention and out Indigenous issues at the centre of the national conversation.[12] Jolene Marr, a Mi’kmaq fisher who used Facebook to share videos of racism and harassment from non-Indigenous fishers, has said that “In the past, we’ve been done wrong by the media. The whole truth not being told, only pieces of the story being told. [These videos] let the light shine on the actual truth. Social media has been a godsend for that.”[13]

Social networks can also be used to broadcast Indigenous arts and culture, as Inuk artist Shina Novalinga does with her throat-singing videos on TikTok. Novalinga has said that “there needs to be more Native representation because for many years, Indigenous culture was misrepresented and forgotten. We are now using our voices on the platform and I think that's beautiful, to be able to find a community that stands with each other. Everyone should embrace their culture and not feel scared or afraid to spread awareness.”[14]

This is why, while noting that social media has its drawbacks – in particular the risks of harassment and exposure to hate content – the Report of the Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls concluded that “social media has the potential to mitigate racist and sexist portrayals of Indigenous women, girls, and 2SLGBTQ+ people by allowing Indigenous Peoples to contribute to their own stories.”[15] Websites such as Turning Point also provide virtual spaces for Indigenous and non-Indigenous people in Canada to gather and communicate; more recently, Indigenous coder Alejandro Mayoral Baños created the Indigenous Friends app, aimed at making a meeting space for Indigenous youth who feel isolated when away form their communities

While there has traditionally been little Indigenous participation in the video game industry, this is beginning to change. Indigenous creators have made games as diverse as Mikan, a digital version of the traditional “moccasin game,” and the first-person shooter Otsi: Rise of the Kanien'keha:ka Legends.[16] Indigenous gamers have also made inroads into the game streaming community with channels like Jon-Ross Merasty-Moose’s Moose Tree Gaming and Marlon Weekusk’s Marmar Gaming, which bring Indigenous culture and viewpoints to a medium that, while very popular among Indigenous youth, has traditionally had little Indigenous representation.[17]

Next section

Resources for parents

Resources for teachers

[1] Statistics Canada. (2017) “The Aboriginal languages of First Natipons people. Métis and Inuit.” Census in Brief. Retrieved from https://www12.statcan.gc.ca/census-recensement/2016/as-sa/98-200-x/2016022/98-200-x2016022-eng.cfm

[2] Final Report. (2019) National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls. Retrieved from https://www.mmiwg-ffada.ca/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/Final_Report_Vol_1a-1.pdf

[3] NoiceCat, J.B. (2019) “Can film save Indigenous languages?” The New Yorker. Retrieved from https://www.newyorker.com/culture/culture-desk/can-film-save-indigenous-languages

[4] Moore, A. (2022) “Glooscap cartoon series recorded in Wolastoqey language an attempt to revive the language.” APTN National News. Retrieved from https://www.aptnnews.ca/national-news/glooscap-cartoon-series-recorded-in-wolastoqey-language-an-attempt-to-revive-the-language/

[5] Ahtone, T. (2018) “Indigenous comics push back against hackneyed stereotypes.” High Country News. Retrieved from https://www.hcn.org/issues/50.22/tribal-affairs-indigenous-comics-push-back-against-hackneyed-stereotypes

[6] CBC Gem. (2017) Keep Calm and Decolonize. CBC. Retrieved from https://gem.cbc.ca/season/keep-calm-and-decolonize/season-1/36c05dc6-138a-4b7c-a987-5313a9c498ba?cmp=sch-decolonize

[7] CBC News. (2017) “Making music video with teens in Indigenous communities helps plan ‘seed of confidence.’” CBC. Retrieved from https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/manitoba/manitoba-garden-hill-music-1.4000524

[8] Woodgate, M. (2016) “App project to help Indigenous youth record and share their stories.” CBC. Retrieved from https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/nova-scotia/app-storycorps-indigenous-youth-record-1.3674948

[9] (2019) National Indigenous Music Study. APTN/NVision Insight. Retrieved from https://corporate.aptn.ca/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/APTN_NIMIS_Report_ENG-UPDATE.pdf

[10] Audet, Véronique. (2005) “Les chansons et musiques populaires innues: contexte, signification et pouvoir dans les expériences sociales de jeunes Innus,” Recherches amérindiennes au Québec, 35:3, 31-38.

[11] Fallon Andy (Anishinaabe, Couchiching First Nation). (2019) Testimony to the National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls.

[12] Rice, W. (2013) “Indigenous journalists need apply: #IdleNoMore and the #MSM.” Canadian Media Guild. Retrieved from https://www.cmg.ca/en/2013/01/29/indigenous-journalists-need-apply-idlenomore-and-the-msm/

[13] Bascaramurty, D. (2020) “Power at their fingertips: Indigenous people turn to social media to expose injustice.” The Globe and Mail. Retrieved from https://www.theglobeandmail.com/canada/article-power-at-their-fingertips-indigenous-people-turn-to-social-media-to/

[14] Allaire, C. (2020) “This Inuk Throat Singer is Bringing Cultural Pride to TikTok.” Vogue. Retrieved from https://www.vogue.com/article/shina-novalinga-indigenous-inuk-throat-singer-tiktok

[15] Final Report. (2019) National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls. Retrieved from https://www.mmiwg-ffada.ca/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/Final_Report_Vol_1a-1.pdf

[16] Lapensée, E. (2017) “Video games encourage indigenous culture.” The Conversation. Retrieved from https://theconversation.com/video-games-encourage-indigenous-cultural-expression-74138

[17] Monkman, L. (2020) “Cree video game streamers create space for Indigenous gaming community.” CBC. https://www.cbc.ca/news/indigenous/cree-video-game-streamers-1.5834861