Sorting Fact from Fiction

Though many Canadians – especially youth – first hear about news on social media, research has found that news outlets’ videos are rarely seen, leaving a gap for misinformation (or intentional disinformation) to fill.[1] While people often overestimate how common misinformation in news actually is, this perception can reduce trust in reliable news sources, as well.[2]

There are three types of news stories that need a particularly skeptical eye:

- Non-news content, such as ads and opinion pieces, that looks like news

- Entirely false news stories, including satire and fake stories that purport to be true

- Genuine news stories which are significantly compromised by the source’s bias

Research suggests that most people judge a news source based in part on whether it looks like news.[3] This can make it difficult to distinguish between genuine news and “native advertising” or “sponsored content” that mimics the form of news: one study found that 82 percent of students were unable to distinguish between a real news story and an ad with similar formatting on the same website.[4] Added to this is the increasingly blurry line between news and opinion and the difficulty of distinguishing between the two, especially in online contexts. While in print newspaper opinion pieces are generally kept separate from news, research has found that fewer than half of news organizations provide any sort of labels to online pieces to help readers tell when they’re reading news or opinion.[5]

The second type – entirely false stories spread by unreliable or fictitious news sources – can have a significant effect in three ways:

- first, when it reaches news consumers who don’t have the general knowledge to know the difference between the (real) Boston Globe and the (fake) Boston Tribune,[6] especially now that it’s relatively easy to create a professional-looking website;

- when it reaches people who are prone to engage in motivated reasoning – the mental habit of working backward from what you believe to your judgment of a source’s credibility, which is associated with having highly polarized beliefs on the topic;[7]

- and when false or highly distorted stories spread from unreliable sources to legitimate news. The blurred distinction between fact and opinion described above, along with the tailoring of news content to narrower audiences, can make news sources vulnerable to their own form of motivated reasoning in which they are more willing to give the benefit of the doubt to stories that align with their (and their readers’ or viewers’) political opinions or biases.[8]

This last point may have the biggest impact. While entirely false news items are the most obvious – almost everyone has a friend or relative who shared a story from The Onion or The Beaverton without realizing it was satire, or has seen made-up stories circulate during an election – it is most often when they spread to a legitimate but compromised source that they reach news consumers.

To find out if a news outlet is worth our attention, we need to use companion reading to research them. That means looking for the markers of reliability that come from the news genre’s norms: knowledge or expertise, a process for verifying and correcting information, and a motivation to be accurate.

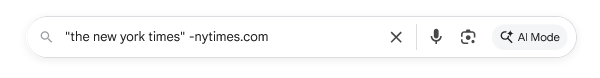

To answer the first two questions, we can look for evidence other than what they say that they are reliable. Many news sources will have Wikipedia pages that will give an overview of their reliability; if not, search for the name of the outlet and then use a minus sign to exclude their own website:

Some independent journalists like Marisa Kabas have broken big stories and had their coverage picked up by major news outlets. Others, like Bisan Owda, have even won journalism awards such as an Emmy and a Peabody. (Of course, there are a lot of awards out there, and your students are unlikely to know the significance of the Peabody award, so remind them to take a moment to research an award before assuming it means anything.)

Looking at their track record can also mean looking at how long an outlet has been publishing or how long an account has been active. If they claim to be publishing original photos or videos, check to see why they would be able to access those and if what they’re posting is consistent over time. (Sharing supposedly first-hand content from many different places is a big warning sign.)

Key signs that a news outlet has a motivation to give you accurate information is doing this include:

A commitment to accuracy. While every news outlet makes mistakes sometimes, frequent errors can suggest that accuracy is not a top priority for them. (Dodging this question by reporting on inaccurate stories spread by other outlets falls under this category, as well.)

A commitment to accuracy. While every news outlet makes mistakes sometimes, frequent errors can suggest that accuracy is not a top priority for them. (Dodging this question by reporting on inaccurate stories spread by other outlets falls under this category, as well.)- It can be helpful to look over an outlet’s front or home page, and opinion pages, to get a sense of what value proposition it is offering to audiences. Is it selling you news that’s accurate, that’s entertaining or that reinforces your identity and belief?[9]

- Openly retracting and correcting errors. Just as importantly, when an outlet does make a mistake, they should be upfront about correcting it.

- Following a story whether or not it supports the outlet’s political leanings or bias. News and editorial (where the editorial board publishes opinion or analysis pieces) should be separate. Failing repeatedly to cover stories that conflict with their position, or focusing most heavily on stories that agree with it, are signs that bias is influencing the coverage.

- Seeking out and presenting different viewpoints. News outlets have no obligation to amplify hate, harassment or pseudoscience, but in general they should make sure that all sides of an issue are represented.[10]

This question can be a bit trickier when it comes to independent journalists, because a big part of their appeal is that they are not objective, giving audiences access to voices and viewpoints that would otherwise be unheard. Instead, teach students to look for transparency about an independent journalist’s point of view. Bisan Owda, for example, has been open that her goal is to document the lives and experiences of the residents of the Gaza Strip, starting each of her videos with some variation on the phrase “It’s Bisan from Gaza and I’m still alive.”

Traditional outlets can take steps to be more transparent about their coverage:

- Openly acknowledging their viewpoint and possible bias. Including not just what is known about a story but what is currently not known, to help consumers tell the difference between genuine gaps and things that have been deliberately left out.

- Whenever possible, link to original sources, such as transcripts and databases, so consumers can verify the accuracy of what’s being reported.[11]

- Some news outlets post their editorial standards or code of conduct, so you can see what steps they take to make sure what they report is accurate. For instance, the Globe and Mail has their Editorial Code of Conduct posted on their website and also runs a regular column by their Standards Editor that explains topics ranging from their corrections policy to why they choose different words or phrases when covering particular issues.

Once you’ve used MediaSmarts’ Break the Fake companion reading tips to make sure a source is worth your attention, visit our section on News to learn how to read between the lines.

[1] Hagar, N., & Diakopoulos, N. (2023). Algorithmic indifference: The dearth of news recommendations on TikTok. New Media & Society, 14614448231192964.

[2] van der Meer, T. G., & Hameleers, M. (2024). Perceptions of misinformation salience: a cross-country comparison of estimations of misinformation prevalence and third-person perceptions. Information, Communication & Society, 1-22.

[3] Chakradhar, S. (2022) People mistrustful of news make snap judgments to size up outlets. Nieman Lab.

[4] Wineburg, Sam, Sarah McGrew, Joel Breakstone and Teresa Ortega. (2016). Evaluating Information: The Cornerstone of Civic Online Reasoning. Stanford Digital Repository.

[5] Iannucci, Rebecca. “News or Opinion? Online, It’s Hard to Tell.” Poynter.org, August 16 2017.

[6] Stecula, Dominik. “The Real Consequences of Fake News.” The Conversation Canada, July 27 2017.

[7] Kahan, Dan. “What is Motivated Reasoning and How Does it Work?” Science and Religion Today, May 4 2011.

[8] Rimer, Sara. “Fake News Influences Real News.” BU Today, June 22 2017.

[9] Hopkins, D. J., Lelkes, Y., & Wolken, S. (2024). The rise of and demand for identity‐oriented media coverage. American Journal of Political Science.

[10] Schudson, Michael. “Here’s What Non-Fake News Looks Like.” Columbia Journal Review, February 23 2017.

[11] Rosen, Jay. “Show Your Work: The New Terms for Trust in Journalism.” PressThink, December 31 2017.